- Home

- Eliza Casey

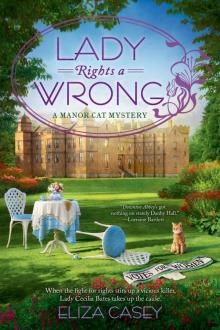

Lady Rights a Wrong Page 4

Lady Rights a Wrong Read online

Page 4

“I’ll stop by after we go to the milliner,” Cecilia said. “It is almost my father’s birthday. And I do quite look forward to seeing Mr. Talbot again.”

They swung around a corner, swerving to avoid an especially large rut on the road, and Cecilia’s brown velvet hat tumbled over her eyes. When she straightened it and pinned it tighter to her coil of hair, they had come into the village itself.

Danby Village, with its green at the center, was as familiar to Cecilia as Danby Hall. In the middle of the green stood an obelisk to memorialize the village’s war dead surrounded by benches and pathways where everyone gathered on fine days. Shops ringed the green with gray Yorkshire stone, dark slate roofs, and shining display windows. Cecilia spotted the Mabrys’ grocery, the milliner, Mr. Smithfield’s florist, the Misses Moffat’s tea shop, the branch of Coutts bank, Mr. Jermyn the attorney, and Dr. Mitchell’s surgery. Just beyond was the whitewashed Crown and Shield pub with its wooden tables lined up in a small courtyard, and the sturdy, Norman-era St. Swithin’s Church with its large yard and pretty brick vicarage. On the corner was her very favorite place, Mr. Hatcher’s bookshop.

The other side of the village housed a row of pretty cottages, and the largest dwelling of all, her grandmother’s dower home.

“Why don’t you wait for us at Mr. Talbot’s shop, Collins?” Cecilia said, gathering up her scarf and handbag. “We’ll come find you there when we finish up our errands.”

“Very good, my lady.”

Jane followed Cecilia along the high street, past Mrs. Mabry’s grocery, Dr. Mitchell’s surgery, and Mr. Smithfield’s florist shop with large arrangements of dark-red roses in the windows. Cecilia was meant to pick up a hat for her mother at the milliner, but she thought she could grab a cup of tea and some strawberry cakes at the Misses Moffat’s tea shop. She was in no hurry to get back to Danby.

“I hope Annabel doesn’t need you back anytime soon, Jane?” she said.

“I think she and Lady Avebury were meeting Lady Byswater about the church bazaar,” Jane answered. “Miss Clarke is very curious about the new renovations the Byswaters are doing on their house, so I doubt they’ll return until after teatime.”

Cecilia laughed. The Byswaters were quite wealthy, thanks to Lord Byswater’s clever investments and Lady Byswater’s inheritance from some factory or something, and they always had a new, lovely bit of house being added, or large stables built and Italian fountains installed in their gardens. They sometimes made overtures about buying some Danby land, but with Annabel that would no longer be necessary. “Wonderful! A whole day of freedom.”

They stepped into the milliner’s shop at the end of the lane and, after a pleasant hour of examining ribbons and feathers, left with Lady Avebury’s new chapeau along with a darling little beret for Cecilia. Large, feathered and bowed, swagged hats were still all the vogue, but Cecilia grew tired of the weight and not being able to see at all to either side of her. Leaving off such styles was one of the advantages of being in the country again. Though she did notice there seemed to be more people than usual strolling the streets and on the green.

“Lady Cecilia!” she heard someone call, and turned to see Mrs. Mabry at the greengrocer arranging a display of brussels sprouts outside her door, along with pyramids of orange and purple carrots and the last of the summer peas laid out enticingly in baskets. “How fortunate to see you. I was just going to send a message to Mrs. Frazer to see if she’d like some of these sprouts, the first of the season. Just arrived.”

“I’m sure she would, thank you, Mrs. Mabry,” Cecilia said. “Her roasted sprouts with béarnaise sauce is one of my brother’s favorites.”

Mrs. Mabry’s smile turned a bit sly, and she wiped her hands on her gingham apron. “And how is Lord Bellham? Any interesting news to be expected soon?”

Cecilia knew very well what she meant. Patrick’s maybe-engagement to Annabel had been the talk of the village all summer, everyone hoping for a grand wedding soon in St. Swithin’s and American dollars to pour into the shops. “He is in excellent health, thank you, Mrs. Mabry, as are we all. And your nephew Mr. Fellows is doing very fine work at Danby.”

“I’m glad to hear it.” Mrs. Mabry glanced down at her display with a sigh. “Though I could certainly use his help here right now. So many people are coming into the village for that Mrs. Price business, I don’t know how we’ll feed them all!”

“Large crowds are expected, are they?” Cecilia asked. That would explain why the village seemed more populated than usual.

“All the rooms at the Crown and Shield are full, and every cottage to be spared is let. I just hope all my vegetables come in time!”

“Of course. I’ll stop on the way back to Danby and pick up the sprouts, and maybe some tinned pineapple if you have it to spare?”

“Right you are, my lady.”

Cecilia took Jane’s arm as they walked away, whispering excitedly, “Did you hear that, Jane? It sounds as if Mrs. Price really will have a great success here!”

“Only if it’s the right sort crowding into the village, my lady,” Jane answered doubtfully.

Cecilia watched as a quartet of ladies in stylish suits strolled past them toward the tea shop. “What do you mean?”

Jane gestured toward a group gathered in the small front garden of the Crown and Shield pub. It was usually quiet there at that time of day, with only a few elderly farmers sitting at the long wooden tables with their pints, talking about the good days of the “old queen.” Today, though, quite a crowd was gathered, their voices rough and loud even at that distance.

To her dismay, Cecilia recognized Lord Elphin at the center of the group, obviously the ringleader of whatever was going on, pounding his hammy fist on the planks of the table.

The Byswaters were Danby’s nearest neighbors, and even though they made no secret of the fact that they would like to acquire some Danby land to expand their own estate, they were friendly and easy to get along with, hosting a grand hunt ball every year that kept the neighborhood on their good side. Lord Elphin owned the estate on the other side of the Byswaters and was a different kettle of fish. Though his family was a very old one, there was little money, and his house was crumbling. He seemed to enjoy drinking and feuding with everyone else in the neighborhood more than trying to restore his fortunes, though he ran his farm as he always did. And his wife, who might have served as some sort of good influence, had died many years ago. The Bateses mostly avoided him whenever possible.

As they came closer to the Crown, Cecilia saw that most of the men gathered around Lord Elphin were his own tenants and farmworkers, a rough lot who seemed as shiftless as their employer. No one enjoyed seeing them in the village, and luckily, they seldom appeared, especially in groups.

Until today.

“. . . won’t stand for it!” Lord Elphin growled, pounding again at the table. His face, beneath the sparse ring of his graying hair and his whiskers, was alarmingly red. “People like that invading our neighborhood. Sluts who destroy private property! When they should be home taking care of their families. Next thing you know, women will be drinking in the pubs while we’re left to mind the kiddies. You better watch your own houses, boys.”

“Tain’t right,” one of Lord Elphin’s men cried.

“He must be talking about Mrs. Price,” Cecilia said indignantly. She started to march toward the Crown, to give that horrid old Lord Elphin a piece of her mind, but Jane held her back.

“My lady, we should just let them be for now,” she whispered. “I know they’re very wrong, but there are only two of us, and they’ve been drinking.”

Cecilia reluctantly nodded. Jane was quite right, of course. Two women against a group of drunken men might not end well at all. Cecilia knew she was often too impulsive, too quick to jump in, when cool, careful consideration, not to mention patience, would be more likely to win the day.

&n

bsp; But her blood still boiled to see Lord Elphin and his cavemen cronies. The village did not belong to them, nor did their wives, who were no doubt locked up at home cooking or cleaning, or both.

“You are quite right, Jane,” she said. “But we must get a message to Mrs. Price before her rally to watch for those bullyboys. They seem just the sort to try and break things up with violence.” She remembered tales of suffrage meetings in London, windows and bottles smashed all around, women beaten, banners torn down.

“Maybe Colonel Havelock should know, as well,” Jane suggested.

“Of course. We can stop at Mattingly Farm on the way back to Danby.”

“Shall we go to the bookshop, then?” Jane said, in that coaxing tone Nanny had once used to employ when cajoling Cecilia into a better humor. It was rather irritating, but Cecilia had to admit it was also rather effective. Jane was coming to know her too well. Stepping into Mr. Hatcher’s bookshop, inhaling that delicious scent of glue, dust, and old leather, always made her feel calmer.

By the time they emerged with a package of the latest French poetry, Lord Elphin and his crowd were luckily gone. But someone equally surprising was on the green, just beyond the war memorial. A tall, burly man in a blue policeman’s uniform held another man by the collar of his shabby coat, giving him a good shake.

Cecilia peered more closely at the bobby. There was something rather familiar about that face beneath the helmet, the pockmarked cheeks and crooked nose. “Is that—Sergeant Dunn?”

Sergeant Dunn had come with his inspector to Danby all the way from Leeds to look into the Hayes matter this past spring. Cecilia hadn’t seen him since then.

Jane gasped in surprise. “I think it is, my lady. Surely no one else looks quite like that. What could he be doing here?”

“Let’s go find out.” Before Jane could stop her, she marched across the lane and along the gravel pathway that wound around the green. “Sergeant Dunn! Is that really you?”

The sergeant looked up, and a grin broke out across his fearsome face, completely transforming him. Cecilia remembered how he had been kind and methodical while his horrid inspector tried to arrest her brother. Was his smile just a bit brighter when he looked at Jane now? “Lady Cecilia, Miss Hughes! Fancy seeing you here.” His grip never loosened on the kicking, protesting man.

“Well, we do live here, Sergeant,” Cecilia said. “But whatever are you doing in Danby?”

“Seconded from Leeds for a few days, to keep an eye on that Mrs. Price,” he said. “There was a bit of trouble when she was in Leeds a few weeks ago, and no one wants that here.”

“Indeed they don’t,” Cecilia agreed. She gestured to the struggling man. “Is he part of this expected trouble, then?”

Sergeant Dunn looked down at him in surprise, as if he forgot he held on to anyone at all. “This? No, he’s just a bit of a lucky find. Georgie Guff, a well-known thief.”

“That ain’t true!” Mr. Guff yelled. “That’s a foul lie. I’m a law-abiding citizen now. I done my time in Wormwood Scrubs.”

“That’s not what I heard, Georgie, not when that jewelry shop was turned over last month,” Sergeant Dunn said, giving him another shake. “I saw him lurking around Mr. Talbot’s antiques shop over there. Eyeing the silver service in the window. A gift for your mam, then, Georgie?”

“No law against looking in windows,” Georgie muttered.

Sergeant Dunn pushed him away, and Mr. Guff straightened his threadbare coat and smoothed his thin, pale hair. “Just stay away from me and out of trouble while I’m here, then, Georgie. We’ve got enough to worry about what with them suffragettes.”

Georgie seemed to agree and ran off without another word, disappearing into the alleys behind the shops.

“Why would a notorious thief from Leeds come to someplace like Danby Village?” Cecilia asked, watching as the man tripped and dodged away. “Unless there is a new profitable line in books and scones.”

“Maybe he’s waiting for Mrs. Price and her group?” Jane suggested. “The ladies we saw walking around today were dressed nicely.”

Sergeant Dunn scoffed. “Lot of coin in smashing lampposts, now?”

Cecilia frowned and decided she didn’t have time to enlighten another ignorant man that Mrs. Price’s Union was much more about intelligent speeches concerning justice than smashing anything. And Danby didn’t have many lampposts, anyway.

“I’ve heard that Mrs. Price’s husband was something high up in the law; he even worked for Queen Alexandra,” Cecilia said. “I am sure Mrs. Price is comfortable without pawning lampposts.”

Jane tapped at her chin in thought. “Didn’t one of her daughters study the law, as well?”

“Yes, Anne Price. At the University of Manchester. She can’t practice, though, even though she took high marks. I think I read she was third in her class.” Cecilia tried to remember what she knew about Anne Price, but all she could recall was that Anne was second-in-command to her mother, along with Mrs. Price’s secretary, Cora Black, and her vice president, Harriet Palmer. She had seemed a quiet, sensible sort when they briefly met at the theater in London. “I think there’s another daughter, as well, who is also married to a solicitor. I don’t think she’s in the Union, though.”

“Very wise of her,” Sergeant Dunn said. “You ladies be careful while rabble like that is around.”

“Oh, we will, Sergeant. And you keep an eye on Mr. Guff. I wouldn’t want my mother’s jewelry to go missing.” Cecilia gestured to where the thief had reappeared, eyeing the marble facade of the branch of Coutts bank. With a curse, Sergeant Dunn took off after him.

Laughing, Cecilia and Jane turned toward the tea shop. “I don’t think Mrs. Price should count the sergeant as an ally,” Jane said.

“But he does seem rather sweet, in his old-fashioned sort of way,” Cecilia said. She glanced at the pub where Lord Elphin and his crowd had been whipping themselves into anger. “Some men, though, are clearly nothing but trouble . . .”

Chapter Five

Oh, Mother, why did you bring that thing? We have cars to take you wherever you need to go,” Anne Price said, scowling as she watched her mother wheeling a bicycle into the flagstone foyer of Primrose Cottage.

Amelia Price patted the handlebars with a fond smile and adjusted the basket. “A car won’t give me exercise in the fresh air I need. A good pedal around the lanes is required if I’m going to keep up with the Union’s schedule. I’m not getting any younger.”

As Amelia took off her stylish straw and satin hat, she revealed a luxuriant pile of dark hair barely touched by gray. Only the faintest of lines surrounded her large gray eyes, though her skin was a touch unfashionably golden from those long pedals, and her stylishly narrow-cut cream cashmere suit made her look even younger.

Anne felt rumpled and worn next to her mother, tall and gawky and dressed all wrong as she always had. She worked so very hard for the cause, studying law, sitting up all night plotting rallies and extracting ladies from jail, and still it was only her mother everyone saw. Her mother who floated through life, as easy as a drifting silk scarf and as bright as a diamond.

Anne sighed. It was always thus, her racing to catch up with her mother and her pretty older sister, Mary. At least Mary had no use for the cause. Quite the opposite.

“Why can you not just go for a walk when you need fresh air, Mother?” Anne asked.

“And what if I need to run an errand while I’m out? I need my basket.”

Anne frowned. “You mean, if you need to fetch more bottles of wine from the pub?”

Amelia just laughed and drifted into the cottage’s sitting room. She tossed her hat and gloves onto a large, round, heavy oak table and sat back on a burgundy velvet settee. The whole cottage was like something from decades ago, all dark wood, small windows, swagged velvet draperies, and waxed flowers under glass. But it was cheap, and

large enough to house some of their committee members and hold meetings. And for storing bicycles.

“Oh, Annie, don’t be such a wet blanket,” Amelia said lightly. “Wine is an art. If only you had paid attention when we were in France.”

“I was too busy studying when we were in France, remember?” Anne said. She glanced out the old mullioned window and saw that the van had arrived, with four men removing their trunks and cases. Amelia preached freedom for women, a lightening of expectations that held their lives tethered, a new simplicity of dress and demeanor. Yet she herself never traveled light.

Anne turned to see that memories of France had indeed affected her mother again, and Amelia was pouring a glass of Bordeaux from her ivory-inlaid carrying case.

“Well, you’re not studying now, my dear,” Amelia said. “Do try some of this; it’s lovely. A ’98.”

“Mother, it’s not even teatime yet. We should go over the plans for the rally. Maybe visit the Guildhall to make sure the stage is set up properly.”

Amelia waved an airy hand, the ruby on her finger flashing fire. Even though she had been separated from Anne’s father for many months, she always wore his rings. “Cora is seeing to all that; there is nothing to worry about.”

“Of course she is,” Anne muttered. Ever since Cora Black had become her mother’s secretary, she had carefully taken over almost every aspect of the Union. The financial books, the logistics of getting members to far-flung rallies like this one, even the ordering of sashes. Between her and the Union’s vice president, Harriet Palmer, there was little for Anne to do anymore. Nor for Amelia, though she did not see and would not admit the way she was being slowly pushed aside and made a mere figurehead, no true work to do at all. “I thought she had been ill for a while?”

“Just a slight fever, I think. It barely slowed her down. I don’t know what we would do without Cora,” Amelia said, closing her eyes blissfully as she drank down half the glass of wine. “She has even agreed to conduct a séance while we’re here. I think this table would be perfect for it, don’t you?”

Lady Rights a Wrong

Lady Rights a Wrong