- Home

- Eliza Casey

Lady Rights a Wrong Page 5

Lady Rights a Wrong Read online

Page 5

“What!” Anne cried. Typing and filing and bookkeeping were all very well, but now séances, too? She knew Cora enjoyed reading about Theosophy, chatting about the Eternal Veil and such, yet she had never seemed to do more than that.

“Yes. She met Madame Breda in Brighton last month; it seems that Madame sensed a great gift in Cora. She must develop it.”

“Here?”

Amelia shrugged. “I don’t see why not. I wouldn’t mind hearing what your grandmother might have to say.” Amelia’s mother had been dead for decades, and Anne knew little about her.

“And give the press even more fuel to declare us figures of fun? Hysterical women who will believe in any nonsense and cannot be trusted to vote rationally?”

“It’s merely a spot of fun, Annie,” Amelia said, pouring more wine. “You worry far too much. It can’t be good for you.”

Yes, Anne thought, she did worry. Someone had to. Their work could change millions of lives, not only their own but those of women who were trapped in existences not of their own making. Unable to use their talents and intelligence, their desire to live as full humans. It was work to change the whole world. Anne knew her mother believed in that, and her beauty and charisma drew followers to her by the hundreds. But Amelia had no care for the hard work behind the drama and applause. Anne took care of that.

Or she had, until Cora Black arrived.

Anne sighed and peered again out the window. She didn’t see the pretty garden, with the last of the climbing roses over the arbor, the vines twining along the fence, the graveled lane beyond, the gorgeous spreading plane trees that cast their shadows over the cottage. She saw all that had happened lately in the Union, all that was happening. Cora had come to them as everyone did, an acolyte of Amelia’s cause, eager to help in any way, recommended by Harriet. Now she did all the tasks. Even illness didn’t slow her down.

And she was a medium now, too, it seemed. Cozying up to the spirits of the dead as well as to Anne’s mother. The living were quite complicated enough.

As Anne watched, a little Topeka Touring car swooped into the drive, so fast it was practically on two wheels, and came to a halt. Cora stepped out, unwinding the gauzy veils of her motoring hat, unbuttoning her creamy canvas duster. She reached onto the seat and pulled out a large, flat box. No doubt the apparatus for calling the dead.

Cora saw Anne watching out the window and waved merrily. Her eyes glowed brightly, and her cheeks were very pink. “Isn’t it the most rustic place you’ve ever seen? Like something in a Hardy novel!” she called.

Anne gave a little wave back. Danby Village was indeed quintessential country England, all half-timbered shops and hedgerows. She just hoped that, like Hardy’s Wessex, it did not conceal wickedness behind every herd of sheep.

* * *

“Oh, Monty! Why must we go to Yorkshire? It’s sure to be gloomy and gray and dull. And you hate spending time with my mother.” Mary Price Winter flopped back onto her chaise, the box of chocolates perched beside her on the satin cushions sliding off and spilling across the rose-embroidered carpet. Her dark hair slipped out of its loose knot and over the shoulders of her ruffled dressing gown.

“That is exactly the point,” Montgomery Winter gritted out between his teeth. He studied himself carefully in his wife’s dressing table mirror, straightened his tie, and smoothed his silk pocket handkerchief. Just because a man was in a bit of a pickle, that didn’t mean he should let the side down.

Especially when he was in a pickle. Appearances counted for everything. And this was all that woman’s fault.

“I don’t understand what you mean,” Mary said.

“I mean—your mother owes you. She had too many distractions here in London to listen to any reason from us, and she hasn’t answered your letter. It will be different in the country. She will have to listen. You must make it up with your mother and sister.”

“Why must I?” Mary cried. “Mother always makes me feel so stupid, and Anne is just a dusty old stick. My headaches have been plaguing me so much of late. We should go to Bath instead.”

Monty slammed his hand down hard, rattling glass bottles and silver picture frames, making Mary sob even harder. “Bath won’t help us now. We need your blasted mother, whether we like it or not. Now, stop being a ninny and get dressed. Something somber and respectable, none of your ruffles and bows. Don’t make me angry again, Mary. I am warning you. Women like your mother and her unnatural harpies might not do as they’re told, as they’re meant to, but it’s a very different matter in my own home. I know you agree with me.”

Mary sniffled and reached for her chocolates. It didn’t matter if her dressing gowns were getting too tight; she needed their creamy comfort now. Sometimes it felt as if no one was on her side. Not her husband, not the mother who ignored her letters, not her stern father who refused to help Monty any longer. No one. “Of course, Monty darling. Always.”

Chapter Six

What do you think, Jack? Do I look quite suitable for a suffrage rally?” Cecilia spun around in front of her looking glass. She had decided on one of her favorite country suits, a light caramel-colored tweed, with a cream silk blouse and sensible, brown lace-up boots. She wanted to look smart and respectable, but not too frivolous.

She straightened her hat, a narrow-brimmed brown felt trimmed with caramel silk roses, and then she remembered seeing photos of Mrs. Amelia Price, dressed in the height of Parisian fashion, with large hats, flounced sleeves, and narrow skirts. She frowned. “Maybe I should dress up a bit more.”

Jack yawned and stretched from his perch on her bed. He didn’t look especially interested, and Cecilia wished Jane was there to offer her opinion. But Jane was occupied in looking after Annabel that evening, as Annabel had a headache, and had forbidden Jane to attend the rally anyway. Cecilia herself had pleaded for an early night after dinner so she could slip out, and she knew she had to leave soon or she would be late. She fastened a small pearl brooch to her brown velvet lapel and reached for her gloves and handbag.

“Wish me luck, Jack darling,” she said. “And don’t tell anyone where I’ve gone!”

Jack blinked his green eyes and sat up on his haunches.

“Very well, you can tell Jane, but no one else,” Cecilia said. “I won’t be late.”

“Mrow,” Jack agreed.

Cecilia carefully opened her door and tiptoed down the gallery to the head of the staircase. She couldn’t hear much; her mother had also gone to bed early, and Patrick was surely back in his laboratory for a few hours. She saw a faint glow flickering from beyond the half-closed door of the music room and heard her father chuckle. He was obviously taking the opportunity to have some more brandy and laugh over the sporting papers without her mother’s disapproving glances. Which meant Redvers would also still be around somewhere.

Cecilia rushed down the stairs, glad of the thick old carpet that muffled her bootheels, and turned toward the dining room. She decided she would slip out the doors to the terrace and then out around the lawn to the road. She was less likely to be seen there than on the front drive.

She hadn’t counted on the dining room still being occupied, though. She ducked around the door only to come face-to-face with Jesse Fellows. Still wearing his livery from dinner, but with a basket in his hands for collecting the silverware, he looked as startled as she was.

Then he grinned.

“Why, Lady Cecilia,” he said. “Eloping in the middle of the night?”

Cecilia straightened her shoulders and tried to look stern. “Nonsense. I was just—feeling a bit peckish. I thought I might see if there was any of Mrs. Frazer’s apple charlotte left.”

“So you came down for a snack in your hat and walking suit?”

Cecilia bit her lip. She remembered how many times Jesse had helped her in the past; surely, she could trust him now? Or a bit of bribery, if need be? “Can you k

eep a secret?”

He smiled and leaned closer. “You know I can, my lady.”

“I’m going to Mrs. Price’s rally in the village. I just don’t want anyone to see me. It’s easier not to argue about it tonight.”

“Oh, I see,” he said with a nod. “And how are you going to get there?”

“I thought I would walk.”

“At night?”

“I do know the way. Papa might usually insist Collins drive us there, but it’s not very far, you know.”

“You still shouldn’t walk in the dark alone. It’ll be late when you come back. I should go with you.”

“Redvers would never let you,” Cecilia protested. “You would get into such trouble, and I would feel awful about it.”

He looked doubtful. He set down the basket of silver. “At least let me hitch up the governess cart for you. You do know how to drive it?”

“Of course. But don’t you have to finish your work in here?”

“It’s just the silver from the sideboard. Mr. Redvers thinks it needs a good polishing. It’ll only take a few minutes to get you set up in the cart.”

Cecilia nodded, glad of his help. They hurried out the terrace doors to the garden, crossing the manicured lawn and the wall of the kitchen garden to the stables. The old medieval tower behind seemed to loom over everything in the shadows, and she could see the light from Patrick’s laboratory. She stumbled on a cobblestone, and Jesse caught her hand. Through their gloves, his fingers were warm and strong, holding her steady. She was rather sorry when he let her go.

In the stables, Cecilia lit a lamp and Jesse brought out the little wicker cart from its stall, along with the placid gray mare who always drew it. The stalls were warm, rich with the familiar old scents of horses and hay, the sounds of snuffles and snorts. It held all kinds of memories.

“You’re very good at that,” she said, watching Jesse’s efficient, calm movements as he hitched up the cart in no time. She remembered how cool-headed and brisk he had been when Mr. Hayes was killed, too, keeping her steady, and she wondered how many other occupational skills he had, who he had been before he came to Danby.

He smiled as he stroked the gray’s soft nose. “My father was assistant to the master of the hounds at the Pryde Hunt near Melton Mowbray, before he died. I spent part of my childhood with such creatures around all the time.”

“And you didn’t follow in his footsteps?”

Jesse frowned. “He died when I was just a lad, and my mum and I moved to London. It’s nice to get outdoors again sometimes, though.” He turned to her with a smile, and that tiny glimpse of his past was gone. “Come on, then, my lady, or you’ll be late.”

Cecilia suddenly remembered the rally, how important it was to be there, and she took his hand to step up on the cart. She suddenly felt a tug at her hem, holding her back.

“What’s this, then?” Jesse exclaimed. “A stowaway?”

Cecilia glanced down to see Jack at her heels, one paw caught in her hem. “You scamp!” she cried. “He must have followed me from the house.”

Jesse tried to pick up the cat, but Jack clung closer to Cecilia with an affronted “mrow!”

“Oh, he might as well come along,” Cecilia said with a laugh. “He does seem determined to demand votes for women.”

Jesse laughed, too, and it made him look younger, carefree. He helped her up onto the narrow seat and settled Jack on a carriage blanket beside her. “I’m glad you’ll have someone with you, my lady.”

Cecilia nodded and flicked at the reins to set out from the stables. She found she was rather glad of that, too.

* * *

The village Guildhall, one of the oldest structures in the neighborhood, dignified, stolid, and square in its darkened medieval stones and cloudy stained glass windows, surely hadn’t seen such excitement in years, Cecilia thought as she left the cart at the livery stable and hurried toward the entry with Jack tucked under her arm. Lights glowed from the opened doors and through the red and blue glass, and she could hear the echo of music and laughter. She glimpsed Mrs. Mabry, Jesse’s aunt, going in, with the Misses Moffat from the tea shop behind her.

A woman was handing out green, purple, and gold sashes at the door. She looked friendly and full of vivid energy, with her pale red curls escaping from their pins. Up close, though, her cheeks were a hectic red in an otherwise pale face, her eyes feverishly bright, as if she wasn’t as healthy as her energy suggested.

“Hello!” she said to Cecilia, offering a sash. “Is this your first time at a meeting? I don’t think we’ve met.”

“It is my first time, yes,” Cecilia said, feeling rather shy as she took the sash.

Jack let out a loud “meow,” making the woman laugh. “And I see you’ve brought a friend.”

“He wouldn’t be left behind, I’m afraid. He won’t cause a fuss.”

“He certainly wouldn’t be the first if he did. I wish I had a little sash for him; he does look so wonderfully fierce.” She shook Jack’s little paw and offered her hand to Cecilia. “I’m Cora Black, Mrs. Price’s secretary.”

Cecilia shook her hand and shifted Jack so she could fasten on the sash. “I’m Lady Cecilia Bates.”

Miss Black’s eyes widened. “Lady Cecilia Bates? From Danby Hall?”

“Yes, that’s me,” Cecilia answered warily.

Miss Black clapped her hands in delight. “We’re certainly glad you’re interested in the cause, Lady Cecilia! Mrs. Price has never been so far north before. She’ll be very happy to hear it’s so receptive to her message. Please, come with me, we’ll find you a seat.”

Cecilia felt her cheeks turn warm. “Oh no, I don’t want to make a fuss. You must be so terribly busy.”

“No trouble at all. Do follow me, Lady Cecilia—and what is young Sir Feline’s name?”

“This is Jack.”

“What a good lad you are, Sir Jack.” Cora scratched him behind his ragged ear and made him purr, which made Cecilia quite like her, too. Jack was a good judge of character.

Cora led Cecilia down the side aisle of the hall. It was a large room, with a vast, hammer beam medieval ceiling and rows of cushioned benches along three aisles, and a dais overlooking it all from the front. Cecilia recognized a few local ladies, like the Moffats, but most of the women were unfamiliar, dressed in white suits and frocks with the sashes. They came to a short row of folding chairs near the front and to the side, with a good view of the dais. It was lined with flowers, no doubt from Mr. Smithfield’s florist shop, large brass buckets of purple, gold, and white blossoms. Behind it were more rows of chairs and a lectern, with a banner hung overhead that read, “How Long Must Women Wait for Justice?” Many of the ladies around the room held placards as well, some of which read, “Women Bring All Voters into the World, Let Women Vote” and “What Will You Do for Women’s Suffrage?”

“Have you worked for Mrs. Price very long, Miss Black?” Cecilia asked as the secretary drew out a chair for her and looked for a cushion for Jack.

“Oh, do call me Cora, please. I’ve only been her secretary for a few months, but I’ve worked for the Union much longer, ever since I left secretarial school.” She gestured to the ladies who sat at the front of the dais, one a plump, middle-aged matron in a navy blue and green dress, and one a tall, slim brunette in a white suit and the Union sash. “That is Miss Anne Price, Mrs. Price’s daughter, and Mrs. Harriet Palmer, the vice president of the Union. We all work together to coordinate the actions of our members across the country.”

“How fascinating,” Cecilia said. And how lovely, she thought, to have such an important cause to dedicate oneself to.

“Will you be comfortable here, Lady Cecilia? Have you a good view?”

“Oh yes, it’s wonderful, thank you.”

“Do come and look for me after. I’ll lend you some of the literature about o

ur work.” She pressed Cecilia’s hand, and her fingers were burning-warm.

“Of course I will,” Cecilia said, and watched Cora hurry away. She did so envy the woman’s sense of energetic purpose, her air of sharp, alert intelligence.

More people were filing into the hall, and Cecilia recognized a few of the women she had seen walking on the green earlier. It reminded her of Lord Elphin and his men, and she hoped they would stay away that night.

She settled Jack on his cushion at her feet and told him, “Now, you stay just there, Sir Jack, and don’t go wandering and interrupting the speakers. You are quite a different sort of fellow from the likes of Lord Elphin, you know.”

He made a huffy “mrow” and started grooming his paw. After a few more minutes, the chatter of the crowd faded away as Anne Price stepped to the podium. “Good evening, everyone. I am Miss Anne Price, Mrs. Amelia Price’s daughter,” she said, her voice deep and resonant. She was more reserved and watchful than her famous mother, but Cecilia could tell she was an accomplished speaker and passionate advocate of the cause. “I cannot tell you how happy we are to visit Danby Village and bring the message of the Women’s Suffrage Union to the north. And now, I am very pleased to introduce my mother, Amelia Price.”

Another woman swept onto the dais, and Cecilia felt a lightning bolt of excitement shoot through her. She slid to the edge of her seat as if she might miss something, even though Mrs. Price had not said a word yet. She had a distinct presence that made Cecilia see clearly why she had become famous. She was tall and lithe, like her daughter, with thick, dark hair swept up and held with pearl combs that shimmered like her white satin gown. She raised her arm, and lace ruffles fell back from her wrists like ocean waves.

“I am so pleased to see such support for our sacred cause,” she said, her voice soft and musical, yet carrying through the ancient hall. “Women’s rights are human rights, and we must spread that message far and wide. Our daughters and granddaughters shall not suffer as our mothers and grandmothers, unable to use their full intellects and talents to achieve their dreams in life. They shall not live at the mercy of men, denied careers and education, simply because they were born female.”

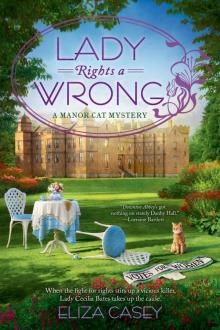

Lady Rights a Wrong

Lady Rights a Wrong