- Home

- Eliza Casey

Lady Rights a Wrong Page 3

Lady Rights a Wrong Read online

Page 3

The dowager countess sniffed. “An overdressed partridge compared to dear Queen Alexandra. I hope that poodle fringe of hers won’t start some unfortunate fashion in ladies’ coiffures now.”

Redvers led the footmen, Paul, James, and Jesse, onto the terrace, all of them bearing tiered Limoges china cake plates of Mrs. Frazer’s prettiest confections. The raspberry tarts, chocolate éclairs, currant scones with lemon curd, and tiny sandwiches of smoked salmon, egg salad, and cucumber and watercress, were laid out like jewels in a shopwindow, shimmering and enticing. Mrs. Frazer’s cooking was renowned all over the neighborhood, and Cecilia’s mother lived in terror of losing her to a grander house that entertained more often.

Annabel, though, was sure to make her mark as a grand hostess once she was Lady Avebury. If she was Lady Avebury.

Redvers laid the silver tea service before Cecilia’s mother, and she poured out the smoky Lapsang Souchong with an elegant, practiced twist of her wrist. Cecilia caught the eye of Jesse Fellows, who stood just beyond Lady Avebury’s chair, and he actually winked at her, the saucy lad. She pressed her damask napkin to her lips to hide a laugh.

“That evening when we saw the king at the theater,” Annabel said, “wasn’t that when those horrid women tried to break the windows of the royal carriage?”

The dowager countess froze as she leaned down to feed a bit of salmon to Sebastian. “Someone tried to attack the king? Dull as the man is, I am sure he doesn’t deserve that.”

“They were suffragettes, Mama,” Lord Avebury said. “It happened as the king and queen were leaving. We didn’t see anything, only heard a bit of commotion. The constables took care of it quite smartish.”

“Suffragettes?” the dowager cried. “Terrible women. In my day, no one would behave like that for something so ridiculous as the vote. It hardly matters who is in Parliament anyway; nothing changes. Now, if someone was flirting with someone else’s lover at a ball, that might be a different tale. I saw two countesses nearly tear each other’s hair out one time at the Duchess of Sefton’s rout.” She snorted with laughter at the memory.

“The suffragettes were causing such a disruption this Season,” Cecilia’s mother said. “Chaining themselves to buildings, blowing up letter boxes.”

“And they tore up the orchid houses at Kew,” Patrick added, sounding as if that was the worst thing anyone could do. “Those plants were one of a kind, invaluable. Why would someone do such a thing?”

“It was not proved who did that,” Cecilia protested. “And if they did, it’s because no one will listen to them otherwise. They just pat them on the head and give them empty promises of support. And that night at the theater, they were only trying to present a petition to the king.”

“You just say that because you want to be one of them, Cecilia,” Annabel said with a little smile.

Cecilia gritted her teeth. She was nearly twenty, and yet they treated her as a child, too. It was not the way it should be. “I am not one of them. Not yet. I merely wish to hear what Mrs. Price has to say when she comes to the village.”

Her grandmother frowned. “Who is this Mrs. Price?”

“She is the leader of the Women’s Suffrage Union, Grandmama,” Cecilia answered. She took a long sip of her tea and then a deep breath to calm herself. “She is going to be holding a rally at the Guildhall, and I’m curious about what she has to say.”

“Oh, dear heavens,” the dowager gasped, and Sebastian growled. He wriggled away from the dowager and ran into the house. “Does that mean we must guard our letter boxes in Danby Village now? And what if you are arrested there, Cecilia? What a scandal. It will be like Lady Constance Lytton.”

“I’m quite sure no one will burn anything down or be arrested, Grandmama,” Cecilia said. “Surely, Colonel Havelock will see to that. And Mrs. Price is not a militant, anyway.” The colonel was the local magistrate, a sensible, no-nonsense military man, a veteran of the Boer War, and very involved in local matters. He had been of great help when Mr. Hayes was killed.

“She won’t be arrested because she won’t be going,” Lady Avebury said. She nodded to Redvers, who discreetly led the footmen away.

“Mama . . .” Cecilia protested.

“I certainly would not attend such a thing.” Annabel sniffed. “Making a public spectacle. So unladylike. I have everything a lady could want right now.” She delicately dabbed at her lips with her napkin, and Cecilia remembered her true history. Eloping from her millionaire father’s San Francisco home, then returning in time to come to Danby, at least according to her cousin. It wasn’t all that “ladylike.” But then, Annabel was so mysterious sometimes.

“I did say we shall not discuss this any further today,” Lady Avebury said firmly, offering a plate of pink-iced petits fours. “It is too lovely an afternoon to spoil with such unpleasantness. Now, Mama, did we tell you what a success darling Annabel was this Season? So many invitations!”

Cecilia half listened as her mother, grandmother, and Annabel chatted about all the London parties they had attended, the latest styles in narrow skirts and lacy sleeves, and studiously avoided any mention of suffrage and rallies. She tried to eat her sandwich, but it tasted like sawdust in her mouth.

“Oh, all the lemon tarts have gone,” her grandmother said with a tap of her stick. “They are Sebastian’s favorites. Where is the little scamp?”

A sudden howl from inside the house, followed by a series of furious barks, said that Sebastian had found his nemesis Jack once again. Surely, Jack needed a puzzle to help solve soon, or he would be forever getting into such scrapes.

“I’ll go call for more cakes—and bring back Sebastian,” Cecilia quickly offered, glad for the chance to escape, even if only for a few moments. Before her mother could protest, she jumped up and hurried through the half-open glass doors. The footmen waited just inside, in case they were needed, and they looked quite surprised to see Cecilia suddenly appear there. They ignored the dog and cat noises, too accustomed to such contretemps by now.

“Just going to see if Mrs. Frazer has any more lemon tarts,” she said cheerfully.

Jesse fell into step beside her. “Let me help you, my lady,” he said, as she made her way through the foyer. The foyer was the one space in Danby most meant to awe visitors, pale, carved stone walls soaring up to a blue-inlaid dome, the Bates coat of arms gilded and shining over the double front doors, tall blue-and-white vases brought from China by her grandfather guarding the entrance. In the corner was a hidden door to the kitchens, her goal.

“Oh, there’s no need . . .” she said.

“I think there is, my lady,” he said with a grin. “Not if I don’t want a dressing-down from Mr. Redvers for failing in my duties.”

Cecilia laughed. “Yes, of course. We can bring more hot water while we’re at it. Grandmama does like her Lapsang, and scolding me is always thirsty work.”

At the door that separated the main part of the house from the narrow stone staircase that led down to the kitchens, they paused. When Cecilia was a child, she had dashed down there without a thought, begging for biscuits from Mrs. Frazer to satisfy her sweet tooth or watching Redvers in careful silence as he decanted the wine, which was almost a religious ritual for him. Now she hesitated to intrude on that busy, bustling world.

“Lady Cecilia,” Jesse said quietly.

She glanced up at him, surprised to see him look so solemn. “What is it?” she said, just as quietly. She had a sudden flash of memory, of when he had saved her from a drunken man’s assault just steps from there in the foyer, and she knew she could trust him.

“I couldn’t help but overhear a bit about that suffrage rally in the village,” he said. “If you want to go, my lady—well, you should go. It’s important to have options in life, for everyone.”

Cecilia remembered that once he had confided he might one day like to be a butler himself, or even own

his own restaurant or hotel. Options in life, ones that a footman might not have had even ten years ago. “Are you a supporter of women’s suffrage, Jesse?”

He gave a wry smile. “I grew up with just my mum and my aunt, my lady.” Cecilia knew his aunt was Mrs. Mabry, who owned the greengrocer in the village, but she had never met his mother. She wondered who she was, where he really came from. “Heaven help anyone who ever tried to tell them what they can or can’t do. They have brains and opinions, just like everyone else. Just as you do.”

He thought she was smart? Cecilia felt her face turn warm, and she tried not to smile. “Why, thank you, Jesse.”

The door suddenly swung open, revealing the green baize on the other side, and Mrs. Caffey, Danby’s housekeeper, stood there. A sturdy, capable woman in black silk, she had been at Danby for decades, since she was a kitchen maid, and now she ruled the household with a benevolent but firm hand. Her eyes widened at the sight of Cecilia, so far from her own tea party and conversing with a footman. Cecilia felt awful, fearing Jesse would get a dressing-down after all. Not that he didn’t seem like a young man who could handle anything at all.

“Is everything quite all right, Lady Cecilia?” Mrs. Caffey asked.

“Perfectly so, thank you, Mrs. Caffey,” Cecilia answered. “My grandmother has requested more lemon tarts, and perhaps more hot water for tea. Fellows here was being most helpful.”

Mrs. Caffey gave Jesse a doubtful glance. “I’m glad to hear it, my lady. I’ll send up more tea trays at once.”

“Thank you.” Cecilia whirled around and departed, walking as slowly as she dared. At the turn of the corridor, she looked back to see Jesse watching her. He gave her an encouraging smile, and she couldn’t help but smile back.

She found Sebastian sitting beside the terrace doors, apparently no worse for wear. And Jack, the naughty fellow, was nowhere to be seen.

Chapter Three

Did you hear?” Bridget, one of the housemaids, whispered to the kitchen maid Pearl. “Mrs. Amelia Price is going to be in the village! You know her. She just got back from a speaking tour in France, telling women they have the right to make up their own minds in life. My own aunt is part of her Union, I think. Now she’ll be here!”

Pearl peeked nervously at Mrs. Frazer, who was carefully stirring her consommé. The tea trays had just been cleared away and dinner preparations were in full action. Even though it was just the family that night, the kitchen was a hive of activity, meats being roasted, trifle being constructed. Pearl herself was meant to be chopping a small mountain of vegetables, but she was caught by Bridget’s words.

“You mean the lady who says we should be able to vote, however we choose?” Pearl whispered back. “She’s going to be right here?”

“At the Guildhall in the village. I saw a flyer about it when I went to my uncle’s bakery this afternoon. It says everyone is welcome. We should go! We might see my aunt there.”

“Oh, I don’t know.” Pearl would like to go, to be sure. It sounded nice to have a choice in life besides chopping carrots forever. But she needed her job. Mrs. Frazer, for all her stern impatience, was a fair woman who said Pearl might even make a cook herself one day, if she worked hard enough. But Pearl was quite sure Mrs. Frazer wouldn’t approve of political agitation on the part of her maids. It could reflect badly on the house, and no one wanted to work in a house that was the subject of gossip.

Yet it was very tempting.

“When is it, this meeting?” she asked.

“In just three days.”

Pearl sighed in disappointment. “That’s not my half day.”

“Well, it’s mine. Maybe that new kitchen maid would change with you.”

“I’ll see about it. I don’t know.”

“What are you two whispering about?” Mrs. Frazer cried. “Here I am, slaving to get this soup finished, and you have time for a gossip! Pearl, those vegetables won’t chop themselves, and there’s the potatoes to roast and the jam for the trifle to finish. And I’m sure Mrs. Caffey is looking for you, Bridget.”

“Yes, Mrs. Frazer,” they muttered together, and Bridget ran up the stairs to find the housekeeper. Pearl redoubled her efforts at the carrots.

The kitchens at Danby were, even with the estate’s recent financial troubles, large and airy. The flagstone floors were scrubbed to a shine even though some of them were cracked, and the walls were painted a bright white. Unlike most kitchens in grand houses, broad, high windows let in plenty of light, so they could see as day turned to lavender-silvery twilight outside the high windows, even now that summer was slipping away and days were getting shorter. Autumn meant more work, since the family was back from London and shooting parties would visit. There might even be engagement celebrations soon. No one was sure what would happen now, but dinner would always have to be on the table at the same time every evening. It was the way Danby was run, and always would be. Properly.

In the adjoining servants’ hall, Mrs. Sumter, Lady Avebury’s maid, brought in her ladyship’s apple-green satin dinner gown to press, and Rose, the housemaid who sometimes helped Lady Cecilia when Jane was busy with Miss Clarke, carried in a pair of silk evening gloves to mend. Redvers soon appeared with the evening newspapers, which Lord Avebury liked to peruse before dining and which had to be ironed to keep the print from smudging off. He scowled in irritation to see that Mrs. Sumter already claimed the iron. It was their nightly battle.

Redvers harrumphed but sat down to glance over the headlines as Mrs. Sumter arranged and smoothed the chiffon ruffled sleeves of the gown. Beyond the door was the crash and clang of the final food preparations for dinner, Mrs. Frazer’s shouts, the clatter of a tray falling to the floor. The aromas of lamb with rosemary and roasted potatoes with the last of the summer peas floated through the warm air.

Mrs. Caffey and Mrs. Frazer came in, the cook with a harried expression on her reddened face and her hair frizzing from under her crooked cap. “The consommé has gone off, just as I feared. They’ll have to have pommes de Parmentier for soup instead.”

Redvers frowned. “Pommes de Parmentier?”

“Will that mess with your wine choice, Mr. Redvers?” Mrs. Caffey asked.

“No, I think the Riesling will still do well enough,” he grudgingly admitted. “But they are having potatoes with the lamb. And one does not like to have plans changed about once they are set.”

“Indeed not,” said Mrs. Caffey. “But one soup instead of another is nothing to the chaos of what happened last spring, I should think. The dining room has been perfectly peaceful since then.”

“Hmph.” Redvers rustled the papers. He did not like to be reminded of the most disruptive thing that had ever happened on his long watch over Danby. “Speaking of chaos—I see that Mrs. Price woman will be here in the village, holding a rally of some sort.”

“Here?” Mrs. Caffey gasped. “Oh dear. I do hope no windows will be broken at Danby.”

“Perhaps his lordship can set some extra guards at the gate,” Redvers said.

“Well, I think someone needs to stand up for us women,” Mrs. Frazer muttered. “We do all the hard work and get none of the credit, and precious little of the money.” She spun around and marched back into her kitchen.

“I’d be so frightened to go to such a thing,” Rose said with a shiver. Her head was still bent over the tear she was mending in Lady Cecilia’s glove, which had no doubt been torn by a cat’s needlelike claws. “All that shouting and pushing, so many people everywhere.” Rose was shy by nature, gentle, wanting only to marry her footman-beau Paul soon and set up her own home.

“They’re not all an argy-bargy like that, Rose,” Mrs. Sumter said, casting a careful eye over the pressed ruffles. “Most of them are only speeches and questions. You might do well to educate yourself, dear. You will have to help teach your children one day.”

Redvers frowned at her.

“I hope you have not been to such a thing, Mrs. Sumter.”

Mrs. Sumter pursed her lips. As her ladyship’s personal maid, she was not actually under the butler’s jurisdiction, and they both knew it. “We must all have our little secrets, Mr. Redvers. I am quite finished here. You should use the iron while it’s still warm.”

Chapter Four

And how is your cousin’s shop faring, Collins?” Cecilia asked the chauffeur as the Bateses’ car jounced along the rutted road into Danby Village. The neighborhood lanes were not quite ready for automobiles, but her father had been one of the first to enthusiastically adopt the technology, including importing a chauffeur from London.

Collins hadn’t been with the family very long, but Cecilia liked him. He was kind and funny, polite without being obsequious, and a very good driver. He had been of great help in solving the Hayes unpleasantness, plus his cousin owned the loveliest little antiques shop, full of tempting things.

Cecilia also suspected Jane might be the tiniest bit sweet on Collins, judging from the way her freckled cheeks blushed and she grew uncharacteristically tongue-tied when they took a drive. She glanced at Jane now and saw that she was distinctly pink.

Cecilia bit her lip to keep from smiling. She did like romance, when it was not her own!

“Business has been quite brisk, my lady,” Collins answered, glancing back at them in the mirror. Did his own gaze linger just a wee bit long on Jane? Cecilia contemplated if she should actually try her hand at a spot of matchmaking.

She wondered what Collins thought of women’s suffrage.

“I’m glad to hear it,” she said. “I do so love that seventeenth-century toilette set he found for me.”

“He said to tell you he has a new snuffbox, Russian enamel, that the earl might like for his collection,” Collins said.

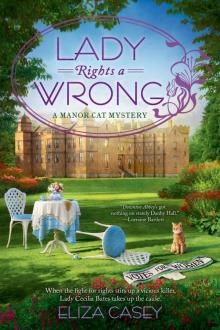

Lady Rights a Wrong

Lady Rights a Wrong