- Home

- Eliza Casey

Lady Rights a Wrong Page 2

Lady Rights a Wrong Read online

Page 2

But Cecilia had begun to wonder if Jane had some romantic notions of her own in life. She did seem to spend quite a bit of her free time in the garage with Collins, the handsome chauffeur. Not that she had much free time, between Annabel’s demands and helping Cecilia.

Cecilia gazed thoughtfully out at the garden as Jane deftly fastened pearl combs into the braids she had just created. It was indeed a warm and sunny day, making Danby look even more beautiful than usual, and marital duties seemed so far away. Yet the thought of them followed her everywhere.

“Have you seen the Blue Lady run across the lawn lately, my lady?” Jane asked.

Cecilia laughed. The Blue Lady was the family ghost, the specter of a Bates who was said to have died in the Civil Wars hundreds of years ago, and who came to visit Danby whenever disaster was near. “Not recently, luckily. She’s only supposed to appear when something terrible is about to happen, you know. I think we had enough of that in the spring.”

Jane shivered. “We did, at that.”

Once Cecilia’s hair was tidied to Jane’s exacting standards, she helped Cecilia out of her plain skirt and shirtwaist and into the fashionable tea gown. She fastened the tiny pearl buttons up the back and smoothed the intricate pleats and lace inserts.

“Do I look like a proper young lady now, Jane?” she asked, twirling her bell sleeves back and forth until Jack leaped up to beat at them.

“Jack, no!” Jane cried, trying to keep his needle-sharp claws away from the delicate lace ruffles. “I do think even the dowager countess might approve, my lady.”

Cecilia sighed. Her grandmama had spent a lifetime learning Society’s rules, and she was always the first to apply them—to everyone except herself. The whole family was quite terrified of her. “I do hope so. I don’t know what I would do without your help now, Jane.” She caught up her shawl and parasol and hurried out of the room, closing the door firmly before Jack could follow. He could help Jane tidy up. Her grandmother, and especially her grandmother’s terrier-terror Sebastian, didn’t much care for Jack, and the feeling was mutual. No one wanted the tea table overturned.

Danby Hall was actually two houses cobbled together as one, older wings from a pre-Reformation priory connected by the grand Palladian mansion her great-grandfather had built. Cecilia’s chamber was in the older wing, and she had to go up and down a few flights of short stairs and along narrow corridors to the old Elizabethan gallery.

She had always loved the gallery, a vast space she and Patrick had played hide-and-seek in when they were children. One of the walls was all windows, curtained in heavy tapestry fabric that half hid the view of the ornamental lake and the medieval tower, while the other wall was dark-paneled wood. Three enormous fireplaces were carved with fruit and leaves and strange, grinning faces that had terrified her when she was a child. Old portraits of Bateses in frilled ruffs and velvet doublets frowned down at her as she passed, interspersed with old battle flags and swords captured by her forebears in battle.

She paused to say hello to Ralph, the ancient suit of armor at the end of the gallery, and patted him on his rusty shoulder before she turned out the door to the main staircase. Local guidebooks to historic houses called it “the best open-well staircase in the neighborhood,” a gorgeous creation of thickly carved dark wood, cherubs, flowers, feathers, elaborate Bs, with niches for sculptures. At the landing hung a portrait by Winterhalter of her grandmother, when she was a young lady at the French royal court. Even with dark ringlets and ruffled pink crinolines, she looked intimidating.

At the foot of the stairs, she was in the “new” Danby, built by her great-grandfather in the latest Palladian style of clean, classical lines and pale colors. She heard the echo of voices coming from the Yellow Music Room, the more informal family gathering place. Her grandmother must not have arrived yet, she thought; she always insisted on being received in the grander White Drawing Room.

Cecilia found her parents, Patrick, and Annabel in the music room, gathered around the white marble fireplace despite the warm autumn day outside the windows. Danby was always rather chilly, with its large rooms and carved stone trimmings. Cecilia wondered if Annabel would install some American central heating once she was Viscountess Bellham, future Countess of Avebury.

If she was ever the countess. The engagement did seem long in coming.

“Ah, there you are, Cecilia,” her mother said with a sigh, as if Cecilia was hours and hours late instead of five minutes. Emmaline Bates had been a great beauty in her youth, and was still very lovely, tall and slim in her stylish green silk gown that matched her eyes, her dark hair barely touched with silver. Cecilia often wished she had taken after her mother, instead of the Bates reddish hair and tendency to freckle. “What on earth took you so long? Your grandmother will arrive at any moment.”

Cecilia crossed the room, pasting a smile on her face. She kissed her mother’s cheek and gave her ancient spaniel a pat on the head. He didn’t even stir. “I’m sorry, Mama, but I’m here now. Can I help with anything?”

Her mother sniffed. “No, it’s all arranged now. Dear Annabel suggested Grandmama might enjoy tea on the terrace, as it will soon be too cold to enjoy the garden.”

“We’ve been chatting about the church bazaar, so exciting,” Annabel said. Annabel, too, was a beauty, golden and ivory and roses like a Sevres china shepherdess, dressed in a ruffled white lace gown and the grand pearls her wealthy American father had gifted her. She was always most enthusiastic about Danby doings, or anything English at all. But Cecilia tended to wonder what really went on behind her large blue eyes.

“And I am sure Cecilia will be most happy to judge the annual cake-baking competition, won’t you?” Lady Avebury said. “Or run the bring-and-buy tent.”

Cecilia, who had been idly flipping through her mother’s copy of The Lady she had found on one of the little gilt Louis XV tables, glanced up, startled at the sound of her name. She did rather tend to daydream a bit when talk turned to her mother’s local activities. One event seemed to be rather like another, even when the cause was one she supported, as she did the new church roof, and she usually ended up fetching and carrying for whatever her mother needed on the day. Annabel was proving much more adept at upholding the Bates duties in the village. She was like a major general organizing a campaign with every Women’s Institute event and charitable assembly.

“I beg your pardon, Mama?” Cecilia said, trying to be all wide-eyed innocence, as if she had really been hanging on every word. “I was just reading about the new winter hats, so riveting.” She had actually been reading an account of a women’s suffrage meeting in London, where the famous Mrs. Pankhurst had evaded the authorities yet again. But that would never do to tell her mother. She had to plan her strategy most carefully to attend Mrs. Price’s rally.

Lady Avebury sighed and ran a bejeweled hand over her sleeping dog’s ears. “Really, Cecilia, you do become more distracted every day. I’m beginning to think we shouldn’t have bothered to take you to London this summer at all. So many dancing partners for you there, and you barely said a word to them.”

“That’s because I know nothing of cricket and had not a jot to add to any conversation, Mama. What is a no ball anyway? Nor have I hunted in ages.” Cecilia did adore riding, racing along with the wind in her face, as if she could take a hurdle and fly free. But it was just the blood and carnage at the end of the hunt she wasn’t interested in at all. And that seemed to be all the London swains cared about.

“It’s a penalty against the fielding team,” Patrick said, glancing up from his botany book.

“What’s a penalty?” Cecilia asked him, puzzled. They were his first words since she’d entered the room. He did tend to live in his own world, one of Latin genus names and such. If he hadn’t been an earl’s heir, he would have surely worked his days away happily at Kew Gardens.

Alas for Patrick, he was an only son, and the D

anby estate and all its problems would one day be his.

“A no ball,” he said. “It’s a penalty against the fielding team, usually the fault of the bowler. That’s about all I know. They tossed me off the village team years ago.”

Annabel gave him a sweet, indulgent smile and patted his hand. “You needn’t worry about such things, Lord Bellham, darling. Emmaline and I have all the village matters well in hand at the moment, don’t we, Emmaline dear?”

Emmaline. Cecilia almost snorted in laughter. American manners. Her mother would never tolerate anyone else calling her by her first name. Not even Cecilia’s father did that in public. But everyone knew Danby needed Annabel’s American dollars.

She set aside the magazine. “What were you saying about the cakes, Mama?”

“That I am sure you would be happy to help out at the church bazaar by assisting, to judge the baking competition this year,” her mother said. “Mrs. Mitchell, the doctor’s wife, always wins for her lemon drizzle, of course, but we must put on a good show. And Mr. Brown is also judging, as he always does. So charming.”

Ah, so that was the purpose of the cake eating. She was to assist the vicar. The handsome, young, eligible vicar. “Surely, everyone would prefer to have Annabel give the prizes. She’s the local celebrity.”

Annabel smiled and smoothed her shining golden curls, also expertly dressed by Jane. “I have made some lovely friends here, it’s true. It feels as if I’ve been here for years, I feel so at home! But I’m already organizing the flower show and the tea tent.”

“And she is presenting the prizes for embroidery work,” Cecilia’s mother added. “Really, Cecilia, you must show some interest.”

Cecilia remembered too well what happened the last time she herself ran the tea tent, all the spilled drinks and toppled strawberry bowls. Judging the cakes should be easier, anyway. “I will try, Mama. But I might be busy around that day. I just learned that someone famous, Mrs. Amelia Price, will be having a rally in the village.”

She knew it was a mistake the minute she said it. Her mother startled so much her old spaniel snorted awake. “That woman! Here?”

“Yes,” Cecilia said carefully. “I thought it was rather exciting. It’s usually so quiet.”

“It is appalling!” Lady Avebury cried. “Don’t you remember what happened in London back in March? All those windows smashed. What if they intend to break up our own village? And right at the time of the church bazaar.”

“That wasn’t Mrs. Price’s group, Mama,” Cecilia protested. “I’m sure this will be most peaceful, just speeches and such. I, for one, am rather curious about what she has to say.”

“Clifford! Can you believe what your daughter has declared?” Lady Avebury turned to her husband with a furious expression. Her delicate, pale, heart-shaped face looked like a thundercloud, and after almost thirty years of marriage, Lord Avebury knew enough to look rather wary. “She wants to rampage through the streets, breaking windows and chaining herself to gates.”

“Cecilia wants to do what?” he said carefully.

“I only want to hear a speech, Papa,” Cecilia protested. “I am not chaining myself to anything.”

“That Mrs. Price is coming to the village,” Lady Avebury said.

“Amelia Price? That votes-for-women nonsense?” Lord Avebury said, his tone puzzled. “I don’t know what she’s on about. You ladies have us to speak for you. Why would you want to do such things, Cecilia?”

“Oh, really now.” Cecilia tossed aside The Lady, feeling ridiculously like a child again. “You are not me, Papa, as kind and dear as you are. I might have my own opinions on things, you know.”

“I don’t see why any lady would want to vote,” Annabel said. “It’s so—unfeminine. What do you think, Patrick?”

Patrick blinked up again from his book. It was obvious he had heard not a word of the quarrel. “What are we talking about, then?”

Fortunately, Redvers chose that moment to enter the music room with a discreet little cough and a bow. Cecilia did think she had done rather a good job on his sketch, with his bushy eyebrows, large nose, and forbidding expression. But she knew that underneath he was a soft heart who had always brought her extra sweets at tea when she was a child. “I beg your pardon, my lady, but the dowager countess’s car has just turned in through the gates. Should I have Rose and Bridget set the linens on the terrace table now?”

Cecilia’s mother took a deep breath and smoothed her face into a serene smile. Long years of being the countess had taught her how to compose herself in any situation. Cecilia wished she could learn how to do that. Her cheeks still seemed to burn with anger simmering inside of her at being treated as a child. But she couldn’t let her grandmother see that.

“Yes, thank you, Redvers,” Lady Avebury said. “We shall be out directly. I think we are quite finished here. Aren’t we, Cecilia?”

Cecilia gritted her teeth. “Yes, Mama.” Yet she knew they were not finished. Not by a mile.

Chapter Two

The terrace of Danby on a sunny autumn afternoon should have been the most idyllic place in the world, Cecilia thought as she followed her mother to the tea table laid out near the marble balustrade. The gardens at Danby were looking especially lovely in the last gasp of summer, autumn golds and ambers touching the leaves, all peaceful and elegant. It didn’t look real at all, after the weeks of crowded London streets, but like a world in a Constable painting. The English countryside, eternal and peaceful, smelling of fresh greenery and the apple-crispness of fall.

Yet Cecilia couldn’t entirely shake the feeling of restlessness and anger that seemed to creep over her like an itch she couldn’t brush away. It had actually been there for months, vaguely humming away in the background as she went about the motions of her everyday life. Changing clothes, sipping tea, looking in shops, dancing, but always as if she was someplace else entirely. Should be someplace else.

That hum was like a shriek ever since she’d heard about Mrs. Price’s rally. Mrs. Price and her cohorts were women with a purpose in life, an important cause. Women who knew how to use their talents and abilities, where Cecilia wasn’t even sure she had real talents.

She glanced back at the tall windows, covered now with heavy red brocade draperies, that led into the grand dining room where Mr. Hayes had been killed last spring in the middle of dinner. It had been a truly awful event, a shocking sight, but Cecilia had surprised herself by dealing with it all. She was needed then.

And now . . .

She just wasn’t sure about anything.

She studied her family, her mother and Annabel chatting again about the plans for the bazaar, some complex bit of maneuvering because Mr. Smithfield’s flower arrangements from his florist’s shop had to be in place before the Misses Moffat from the tea shop brought in the urns for the tea tent, and her father and Patrick studying the lawn before them in the midst of their own thoughts. No doubt her father was envisioning the days of shooting to come, while Patrick wished he was in his laboratory. They all loved her; she knew that. Even her mother cared, despite her constant faultfinding. They wanted the best for Cecilia’s life. But maybe their ideas of best were not really her own. The wide world was changing fast, but Danby always stayed the same.

The glass doors to the terrace opened, and Redvers announced, “The dowager countess, my lady.”

“Oh, Redvers, surely I am quite capable of announcing myself. Or perhaps it is meant as a warning?” Cecilia’s grandmother said with a hoarse laugh as she swept onto the terrace, her ebony walking stick click-clacking on the flagstones. She was no longer the dark-haired, crinoline-clad beauty of her Winterhalter portrait, but her eyes were just as bright blue and piercing, just as all-seeing. She stood straight and erect in her gray velvet and lace suit, her hair thick and silvery-white beneath her velvet toque. Her Scottie dog, Sebastian, trailed behind her, not snapping and growling

for once.

“Mama,” Cecilia’s mother said, hurrying to make sure her mother-in-law’s chair was carefully placed in the shade. “We are so happy you could come today. We thought we should take advantage of these last fine days and have our tea out here. It’s lovely, don’t you think?”

“Are you quite sure it’s not too breezy, Emmaline?” the dowager said.

Cecilia’s mother’s smile stayed carefully in place. “If it becomes too chilly, we can simply move into the White Drawing Room. Is that not so, Redvers?”

“Indeed, my lady,” the always unflappable butler answered. “Shall we bring out the rest of the tea service, then?”

“Yes, thank you,” Lady Avebury said. “I am sure you’ll want to hear all about the London Season, Mama, since we haven’t seen you since we returned.”

“Hmph.” Cecilia’s grandmother waved her stick in the air, as if to banish any hint of Town from her presence. “Much the same as it was in my day, I’m sure, when my husband took his seat in the Lords. Overcrowded ballrooms and too many carriages in the park. One does hear the new king is quite dull.”

Cecilia’s father laughed. “Compared to good old Bertie, how can he help it? King George fell asleep in the royal box at the theater one evening when we were there. Remember, Emmaline? Snoring away while the queen tried to ignore it all.”

Cecilia giggled at the memory of that evening, King George nodding away while Queen Mary, sparkling like Aladdin’s cave in all her diamonds, stared fixedly at the stage, but her mother gave her a stern frown.

“King George and Queen Mary are most worthy, I am sure,” her mother said. “We saw Her Majesty at the British Museum one afternoon, as well, looking at the new Assyrian friezes; she is so cultured. She had the loveliest silver velvet hat. And she did speak so kindly to us at the palace garden party. I am sure she will wish Annabel to be presented next year.”

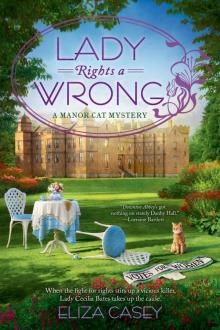

Lady Rights a Wrong

Lady Rights a Wrong