- Home

- Eliza Casey

Lady Rights a Wrong Page 7

Lady Rights a Wrong Read online

Page 7

Those windows looked out onto the front garden, beyond to the lane and all the passersby of the village.

“Lady Cecilia, so marvelous to see you again.” Amelia glided forward to take Cecilia’s hand in a cloud of heavenly rose and wine scent. She wore a morning gown of lavender cashmere and chiffon, the sleeves and high neck embroidered with tiny crystal leaves that matched her earrings. She still wore her ruby ring. An impressive double row of perfectly matched pearls nestled creamily against the chiffon panel of her bodice.

“Amelia, this is Lady Cecilia’s friend, Miss Jane Hughes,” Cora said.

“So lovely! We’ve met so many wonderful people here in Danby. I was just telling Anne that we must establish a northern branch of the Union.”

“But we don’t have anyone suitable to run it at the moment, Mother,” Anne protested. She sounded weary, as if this was an argument she’d had many times before. “We are all needed in London.”

Amelia waved this away with a sweep of her lacy, bell-shaped sleeve. “I’m sure the right person will be found in no time. When a need appears, so does the solution.”

Mrs. Palmer and Cora exchanged a long glance, as if they doubted it was quite as easy as all that. Amelia was the queen, and they were the worker bees.

“Do join us for tea, Lady Cecilia, Miss Hughes,” Amelia said, ushering them toward the cozy grouping of chairs and settees by the fire. Anne seemed to shake away her irritation and gave them a polite smile as she arranged the tea service where the papers had been. Harriet Palmer tucked them away into locked drawers, and Cecilia longed to know what they said. Harriet, though, was still quiet and warily watchful.

“Or perhaps you would care for something else?” Amelia continued. She sat down on a throne-like velvet and gilt armchair, arranging the froth of her long skirts around her. “I do have a lovely pinot gris from Alsace.”

Cecilia glanced at the clock on the mantel, a Black Forest confection of tiny couples in lederhosen and dirndls. It was almost noon now, and there was that whiff of wine under the rose scent Mrs. Price wore. It felt quite daring. “That sounds scrumptious. Thank you, Mrs. Price.”

“Oh, Amelia, remember! And you must call us all Cora and Anne, too, and even Harriet. Just ignore her sour frowns. I am sure we will all be great friends.”

As Amelia uncorked and poured glasses of the shimmering, golden wine, Anne went on with the teacups, her lips pursed.

“I must say I did enjoy the rally so much,” Cecilia said. “It has made me think of, hope for, things I dared never even say before.”

“That is the point—to open women’s eyes to their true potential. We’ve done tours to America, you know, Lady Cecilia, as well as France and Germany. Poor Cora here was quite ill in France, but their spas are the best in the world, and luckily they did wonders for her!” Amelia said. “We were well-received everywhere. Now I see I must reach every corner of our own country, as well. England is much bigger than it looks.”

“I heard you had a break-in last night,” Cecilia said, taking a salmon sandwich from the flowered china plate Anne offered. She recognized the sandwich as the Misses Moffat’s creation. Anne gave a tight smile. She did look much like her mother, with her cameo features and dark hair, but she was all edges and anger where her mother was soft persuasion. Cecilia rather felt for her; she did know what it was like to live in a mother’s perfect shadow.

Amelia looked confused for a moment, before she waved away the break-in with her wineglass. “An attempt, perhaps, but no one got in and we heard nothing, thankfully.” She put a protective hand over the impressive pearls at her throat.

“We have guards in London, ladies of the Union who have been taught a self-defense course,” Anne said. “But Mother thought them unnecessary in the country. Though she will travel with her jewel case rather than leave it at the bank.”

“A lady must be properly attired, my dear,” Amelia said. “A ballot box, and pearls and a stylish hat, can go together. I do wish you would think of that sometimes, darling.”

Cecilia glanced at Anne, at her austere expression and plain dark suit. Anne held her head high and did not answer.

“Is someone here a spirit medium?” Jane asked, thankfully breaking the awkward moment. She nodded toward the dark, solidly Victorian round table in the corner. “I see you have a crystal ball and tarot cards.”

Cecilia was surprised. She didn’t know Jane was a connoisseur of the spirit world.

“That would be me,” Cora said solemnly, quietly.

“Madame Breda said she has great gifts,” Amelia said. “And Madame Breda is a leading member of the Psychical Society in London.”

“I’m just an amateur, though I’ve had unusual gifts and feelings ever since I was a small child,” Cora answered. “I was sure a house of this age must contain many entities, and I thought it could be fun to contact them, hear their stories.”

“How fascinating,” Jane said. “Have you been successful?”

Cora gave a rueful smile. “Not yet, I’m afraid.”

“You live at Danby Hall, do you not, Lady Cecilia?” Harriet asked, speaking for the first time. She sounded hoarse, rather rough and low. Her small, dark eyes glittered with curiosity—or maybe malice.

“Yes,” Cecilia answered, shaking off Harriet’s strange gaze uneasily. “I’m sure we have our share of ghosts, though I’m disappointed to say I’ve never actually seen one. Though my brother used to try to frighten me with the speaking tube in the nursery.”

“When I met your father, so many years ago I hate to think of it,” Amelia said, “he liked to scare all of us silly debs with tales of the Blue Lady.”

Cecilia wondered again how close her father and Amelia had once been for him to have told her about the spirit of her ancestor—and did he remember her now? Her father seldom mentioned the Blue Lady to anyone. “She’s an ancestress from the time of the Civil War. They say she appears when disaster is about to befall a Bates.”

“Then it sounds as if you’re lucky she hasn’t appeared to you,” Harriet said.

“Indeed,” Cecilia agreed. “I would probably scream my head off if she did, or run and hide in the linen cupboard. I’m quite a coward at heart.”

“I’m sure that’s not true, Lady Cecilia,” Amelia said. “You seem quite interested in new ideas. You came to our rally, after all, and faced down that dreadful Lord—oh, what’s his name?”

“Lord Elphin, Mother,” Anne said, slicing the Victoria sponge from the tea shop. It looked like the Prices were settling well in the village, finding the best shops and making acquaintances.

“Lady Cecilia is not a coward at all,” Jane declared loyally. “She even caught a murderer in her own home last spring!”

“We caught him, Jane,” Cecilia murmured.

Amelia grinned. “Oh, how fascinating! I do love a detective novel. Tell us more.”

After Cecilia and Jane told the tale of the murder of Mr. Hayes, everyone looked at them like they were marvels.

“Oh, Lady Cecilia, I am quite sure you and Miss Hughes are exactly the sort of people we need here in Yorkshire,” Amelia said. “Don’t you think so, Anne?”

“I certainly do, Mother,” Anne answered, with a rare smile.

“I—well it’s certainly something I would like to think about,” Cecilia said slowly. “And tell me, Miss Price, is that your bicycle I saw in the garden?”

Anne looked surprised at the change in subject. “No, it’s Mother’s.”

“It is the finest exercise to be had, Lady Cecilia,” Amelia said, pouring herself another glass of wine. “Are you a cyclist yourself?”

“No, but I would like to learn,” Cecilia answered. “I often have errands in the neighborhood, and a bicycle would make it so much easier.”

“A bicycle can greatly aid in a lady’s freedom,” Amelia said emphatically. “We can’t

always rely on handsome young men and their carts. I can teach you to ride, if you like.”

“I would love that. Thank you, Amelia,” Cecilia cried happily.

A knock suddenly sounded at the door, loud and rapid, making them jump.

“Oh, who on earth can that be?” Amelia asked, a touch of irritation to her tone. “We don’t have any committee meetings until this afternoon.”

“Aren’t you expecting Nellie today?” Cora asked.

Anne glanced out the window. “I don’t think it can be Nellie. Unless she’s bought herself a Mercedes HP.”

There was another knock, even louder and more impatient. “I’ll go see,” Cora said, hurrying out of the room.

“. . . about time!” a man’s voice echoed through the foyer. “. . . kept standing on the doorstep like a tradesman. But one can’t expect a proper household here, can we?”

“Oh no,” Anne whispered. Cecilia looked at her, startled to see that the usually unflappable, stoic Anne had gone pale.

Amelia rose to her feet just as two people burst into the sitting room, Cora hurrying behind them. The man was tall, well-fed, and full cheeked, with bushy, graying brown sideburns and a goatee below a gray bowler hat. His brown eyes were narrow and close together, giving him the look of an unfortunate badger.

The woman who hovered behind him was shorter, slighter, very pretty, with an impressive bosom, in a tan lace and muslin dress under her half-unfastened canvas motoring coat. Dark curls escaped like a cloud from the veil of her hat, and her hands fluttered as if she didn’t quite know what to do with them.

“Whatever are you doing here?” Amelia cried.

The lady gave a tired little smile. “Hello, Mother. Monty and I just wanted to see how you were faring. Who would have imagined you here, in Goldilocks’s cottage?” She giggled. “One never knows what might happen next . . .”

Chapter Eight

The next day was Sunday, and Cecilia knew she wouldn’t be able to escape her family duties to go back to Primrose Cottage. There was the church service, where she had to (badly) play the organ, and luncheon at the dower house with her grandmother. Yet she couldn’t stop thinking about the people she had met at the rally, and then at the cottage: Mrs. Price, her daughter Anne, her secretary Cora, and the strangely quiet Mrs. Palmer. And then the Winters couple.

“How Amelia Price could raise such a conventional daughter as Mary Winter, one would never know,” Cecilia said as Jane put the finishing touches to her hair. Jack lolled in a patch of sun near the window, lazily batting at his ribbon. “Though I suppose we all have relatives we wish would stay far away.” She grimaced to remember her father’s cousin Timothy and his damp, lecherous hands.

Jane laughed. “My uncle, my mother’s brother, was always off in Atlantic City dreaming some get-rich-quick schemes. Mines in Ecuador; desalination stations in the middle of the ocean; selling cut-rate petticoats door-to-door. He spends a lot more on those cockamamie ideas than he ever gets out of them. He went off to South America a few years ago, and we haven’t heard from him since.”

“My grandmother’s sister did something like that. She went to explore Lebanon. But she was a marchioness, so no one really cared. She was just thought to be eccentric, not crazy.”

“Sure. If you’re poor, you’re insane. If you’re rich, you’re an individual,” Jane said, biting her lip as she placed a comb carefully at the back of Cecilia’s hair.

“Too true, Jane. Which would people call the Prices, I wonder?”

“From what I’ve read in the papers, my lady, a lot of people would call them sensible. And a lot would call them crazy.”

“Or maybe eccentric? Those pearls Mrs. Price wore weren’t cheap, and someone went to the trouble to try and break into their cottage. After her jewel case, maybe? Or those papers Mrs. Palmer locked away?”

“Traveling abroad can’t be cheap, and didn’t they say Miss Black went to a health spa? I think I did read that Mr. Price is a solicitor, one who did some work for Queen Alexandra herself, but the couple no longer lives together. Maybe that was why he was left off the last Honors List.”

“Interesting. I wonder if it’s because they just don’t get along, or because Mr. Price knows his wife’s work is important so he lets her lead her own life.”

“Then he’d be a very unusual gentleman.” Jane put the last touches to Cecilia’s hair and reached for the navy blue and lavender dress that hung on the wardrobe door, freshly pressed.

Cecilia stepped into it and stood still as Jane fastened the lavender pearl buttons. “What did you make of the Winters? There didn’t seem to be a great deal of love lost between them and Amelia and Anne. I wonder why they came all this way. Perhaps we shouldn’t have departed right after their arrival. A little nosiness can go a long way.”

Jane smoothed the lavender feathers on Cecilia’s navy blue hat, fluffing at the net veiling. “I doubt even a family like the Prices would air their dirty laundry in front of everyone, my lady, especially not an earl’s daughter they’re wooing to their cause. But you’re right—them showing up like that seemed strange. Most people want to stay far away from family members they feud with, don’t they?”

Jane sorted through the glove box and held up a pair of fine lavender kid gloves embroidered with small blue flowers.

“Those look perfect,” Cecilia said. “And the hat, too. Fashionable enough for my mother, but not so heavy I’ll have a headache throughout Mr. Brown’s homily.”

Jane gave a teasing smile as she pinned the hat in place. “And how is the handsome vicar, my lady?”

Cecilia bit her lip, remembering the conversation she had overheard between her parents last spring, speculating on a match between her and Mr. Brown, considering he was going to be Archbishop of Canterbury one day—maybe. “Oh, don’t you tease, too, Jane! I’m sure Mr. Brown has no interest in me at all.”

Jane smoothed the hat’s veil. “I wouldn’t say that, my lady. He comes to call on Lady Avebury about the bazaar all the time, and he always asks after you. Rose said he was very disappointed yesterday to hear you had gone to the village.”

Cecilia shook her head. “I’m sure Mr. Brown knows I would make a terrible vicar’s wife. I am far too unorganized and scatty.”

“I don’t know, my lady.” Jane held out a navy blue shawl. “A vicar’s wife should be caring and concerned about people, and you have that in spades.”

“Do you really think so, Jane?” Cecilia asked hopefully.

“Of course. You’re always the first to offer help, to organize a fundraiser or take donations to people’s homes, to rescue a kitten and run a charity bazaar, even when you don’t want to. You even want to help women get their rightful votes.”

“But could a vicar’s wife really attend suffrage meetings?”

“Are you going back to see the Prices, then?”

“Yes. Apart from anything else, Mrs. Price promised to show me how to ride a bicycle.”

Jane handed Cecilia her handbag and parasol with a grin. “A bicycle would be an excellent way for a vicar’s wife to visit parishioners, my lady.”

Cecilia laughed. “Oh, Jane! Then you should marry Mr. Brown’s new curate, and we could make a parishioner-visiting, mystery-solving team.”

“Except you would never get me on a bicycle, my lady.”

A knock sounded on the door. “The car is waiting downstairs, my lady,” Redvers called.

“Thank you, Redvers, we will be there directly,” Cecilia answered. “And as for you, Jane—no more teasing! I have no intention of getting married just yet. I have a few things to do first.”

If only she knew what those things could really be . . .

* * *

St. Swithin’s Church in Danby Village was not the most elegant church in the county, perhaps—it was too square, too plain, too solid, an old Norman church that had once

formed the chapel of a larger monastery that had long ago been swallowed by the village. Yet Cecilia had always loved it, loved its quiet solidity, its hushed coolness within the thick ancient walls, the scent of candle smoke, flowers, and old dust from the prayer books. One of the stained glass windows, the largest over the altar, was in memory of her great-grandfather, who had restored the old bell tower and bought a new organ, and generations of Bateses lay in the vault beneath the stone floors and in the churchyard. When she was a little girl, she had imagined they would gather close and listen to the hymns with her.

Today, as she filed in behind her mother to the Bateses’ pew just below the spiral staircase to the carved lectern, her thoughts were on more worldly concerns. On the future, and her place in it. She glanced across the aisle to see Amelia and Anne Price, along with Cora Black, all dressed in stylish London fashions for the service, though Amelia’s hat was by far the largest of anyone’s except Lady Byswater’s. Cecilia didn’t see the Winters anywhere.

She waved at Amelia, who smiled and waved back with her lace-gloved hand, but there was no time for any other pleasantries as the organ signaled the opening hymn. Lady Byswater usually played the opening songs, while Cecilia played the interlude. She opened her prayer book and rose to her feet with everyone else as Mr. Brown and his new curate (who was handsome, and would look quite nicely next to Jane) processed down the aisle.

Mr. Brown, too, was good-looking, Cecilia had to admit. Tall and classically handsome, with glossy brown hair and a kind smile, the sort of vicar who might appear in a romantic novel. Not a Mr. Collins in the Austen vein at all. He also seemed kind and cheerful, energetic in his duties, and certainly hardworking. Their last vicar had been at St. Swithin’s for decades and had long since lost the energy to even deliver a coherent sermon, let alone perform the charitable work of the neighborhood. Mr. Brown had come like a fresh breeze through Danby, energizing not only the church but the school, the WI, and all the charitable committees.

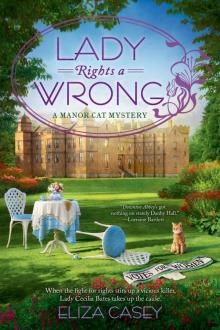

Lady Rights a Wrong

Lady Rights a Wrong