- Home

- Eliza Casey

Lady Rights a Wrong Page 12

Lady Rights a Wrong Read online

Page 12

“Add Lord Elphin to the list, then, Sergeant,” Inspector Hennesy said.

“But do be careful,” Jane said with a smile to the sergeant. “They say Lord Elphin likes to shoot at trespassers.”

“What else have you seen, then, Lady Cecilia?” the inspector asked.

Cecilia tried to think of everything she had noticed in the last few days. “There seems to be some quarrel between Mrs. Price and her elder daughter Mrs. Winter, as well as with Mr. Winter. I’m sure you noticed that when you tried to speak to Mrs. Winter.”

“What sort of quarrel, my lady?” Sergeant Dunn asked.

“I’m not sure. Family differences,” Cecilia said. “Politics, maybe. I don’t think they had seen each other in quite some time until the Winters came to Danby Village.”

Inspector Hennesy scribbled some notes. “And is there anything else you can tell us?”

Cecilia remembered her last encounter with the inspector, when he had been so sure Patrick was guilty of killing Mr. Hayes and almost missed the real culprit, and she wasn’t sure how much she should tell him now. “Not really, Inspector. I had really only just met Mrs. Price, though I did admire her a great deal.”

He snapped the notebook shut and rose to his feet, the sergeant hurrying to follow him. “Then if that’s all, I will take my leave. You and Miss Hughes know you must attend the inquest at the Crown in two days?”

“Yes, of course. Thank you, Inspector Hennesy.” Once they had left, Cecilia and Jane fell back onto their chairs with sighs.

“What do you think, my lady?” Jane said. “Will he just declare it all an accident and go away as fast as he can?”

Cecilia frowned. “I don’t know, Jane. Maybe it was a fall.”

“Do you really think that?”

It was certainly possible. Primrose Cottage was an old, dimly lit place. But where was Mrs. Price’s ring, and the piece of her sash? What about the voices that were heard? “My instinct says—probably not, Jane.”

Jane nodded. “So does mine.”

“But I do think the inspector will try to hurry things along and be done with it, just as he did with Mr. Hayes. Why don’t you talk to Bridget when she gets back, and maybe ask Collins about what Mr. Talbot saw? I can ask around more about any gossip pertaining to the Prices and their family relations.”

“Very good, my lady.” Jane hurried away toward the garage.

Through the window, Cecilia saw her father appear from around the West Wing of the house clad in dusty walking tweeds. She waved to him and pushed open the glass to call out to him.

“Cecilia, dear, what a surprise to see you downstairs at this hour,” he said. “Did I just hear a car drive away?”

“It was Inspector Hennesy, Papa. Perhaps you remember him from the Mr. Hayes business?” Cecilia said. “He’s here looking into Mrs. Price’s death and had a few questions.”

Her father frowned. “Cec, dear, you should have let me or Mr. Jermyn call on him before you talked to him.”

“Oh, Papa, I’m hardly a suspect. It was only a few questions. No need to bother Mr. Jermyn.”

“Nevertheless, my dear, I don’t want you mixed up in this business any more than is strictly necessary,” her father said. “There is bound to be gossip.”

“I’ll be careful, Papa. I promise.” Cecilia leaned out of the window. “I understand you once knew Mrs. Price, yourself,” she said slowly, hesitant to bring up such a personal topic with her father. And he certainly didn’t seem to approve of Mrs. Price’s work now.

“Me? Know a suffragette?” he scoffed.

“When she was Miss Amelia Merriman, a long time ago. She said all the young ladies were in love with you back then. Perhaps it was even before you met Mama.” Cecilia well remembered the tale of her parents’ young romance, her mother the daughter of a respectable but not well-off family of colonial administrators serving in India and South Africa, but so beautiful and charming she won the then-wealthy earl.

Her father’s mouth gaped for an instant. “Miss Merriman? How extraordinary. Who would have thought she would become a suffragette, of all things? Though she was opinionated, even back then . . .”

“So you did know her?”

“Everyone knew her. She was the ‘Diamond of the Season’ according to the gossip papers back then, until she ran off with some attorney. So she turned out to be a suffragette? So odd.”

“She eloped with Mr. Price?”

“I don’t know the details. Gossip was always such a bore. I think her parents didn’t quite approve of him. I suppose no one knew Henry Price would end up attached to the household of Queen Alexandra back then.” He tapped his walking stick thoughtfully on the grass. “Maybe your grandmama would remember more. She was working so hard in those days to get me married off, she knew everyone.” He laughed ruefully. “Mothers don’t change, do they, my dear?”

Cecilia thought of her own mother and nodded in agreement. Had it been thus with Mrs. Price’s mother, or even with Mrs. Price herself when it came to her daughters? It was something that seemed worth looking into.

* * *

Jane found Bridget in the walled kitchen garden, gathering a basket of mint for Mrs. Frazer’s dinner. She looked like a painting of “country contentment” as she bent over the plants along the brick wall, but Jane thought she also seemed deep in thought. Jack trailed behind her, as if hoping for a tidbit.

“Is this part of a housemaid’s job, then, Bridget?” Jane asked, striding along the narrow pathway between the neat beds of vegetables and herbs.

Bridget looked down at her basket with a laugh. “Not really, no. I just like getting outside once in a while, so I told Pearl I would fetch it. A housemaid could go weeks just seeing the inside of walls, you know.”

Jane nodded. She herself was a city girl born and bred, used to being indoors or out on noisy streets, but she had to admit she was getting used to the lovely, green quiet. “Did you grow up in the country?”

“In Danby Village, with my uncle at his bakeshop, after my parents died. I had to work in the shop, but otherwise I could wander a bit in the woods and on the lane.” She glanced back at the house, gleaming in the sunlight beyond the walled garden. “Not much wandering here, but the pay is good and the people nice. I’ve heard of worse situations.”

“So have I,” Jane answered. She remembered the hotel in New York, the men waiting to pinch unsuspecting maids. No one behaved like that at Danby, at least not in recent days. “And Mrs. Harriet Palmer is your aunt-in-law? The woman from the Women’s Suffrage Union?”

Bridget nodded. She bent down to give Jack a bite of vegetable. “My uncle’s sister-in-law.”

“Do you know her very well? And her work?” Jane picked a clump of mint to add to the basket.

“Not well. She lived in London when I was little, still does, I suppose. She was widowed a long time ago. She visited sometimes and always had such interesting things to say about her work. So different from my life.”

“Is it still interesting? Mrs. Palmer’s life? You’ve seen her since she came to the village?”

“Just for tea at my uncle’s house. She’s been even busier lately! She was even in jail for a while, for trying to give a petition to some MP. Just imagine! I could never be so brave.”

“She must be upset about what happened to Mrs. Price.”

Bridget frowned. “It’s hard to tell with Aunt Harriet. She just says the Union needs some fresh ideas.”

“What sort of fresh ideas?” Jane asked, wondering if such a thing could drive a woman like Mrs. Palmer to murder. It seemed unlikely, but then look what had happened to Mr. Hayes last spring.

Bridget frowned, obviously uncomfortable with having such a conversation with her employer’s maid. Jane gave her a reassuring smile, and Jack helped by touching Bridget’s foot with his soft paw. “I’m not sure,” Bridg

et said slowly. “Some of what she says is confusing. But maybe less talk, more action. It’s confusing to me.”

“And she is going to lead this march forward into more boldness? I’m sure the Union needs a new leader now.”

“Maybe. She does get passionate when she talks about it all. She says Mrs. Price could be too slow, too considering. Women need the vote right now. Even I can see that.” Bridget suddenly sighed deeply and rubbed Jack’s velvety ear. “It must be nice, don’t you think, Jane? Doing something so many people think is important. Something that could change the whole world.”

“Have you never thought of going to London to live with your aunt, Bridget? To see what her work is all about firsthand?”

Bridget laughed. “Me, go live in London? I wouldn’t know what to do. I would just bumble around getting in Aunt Harriet’s way. Besides, my uncle needs my wages.”

“Bridget!” Mrs. Frazer called from the doorway. “Where are you with that mint? My lamb’s sauce won’t make itself while you dillydally about.”

“Coming right away, Mrs. Frazer!” Bridget called back. She gave Jane a quick smile and hurried out of the garden with her basket.

Jane thought of what she had learned, that Mrs. Palmer was indeed not happy about the pace of the Union under Mrs. Price’s leadership. Would a woman like that take drastic steps to get what she wanted, when it came to a cause she was so passionate about?

She was needed to help Miss Clarke dress for dinner, but for just a moment Jane wandered to the gateway that led from the garden across the gravel drive to the garage, carrying Jack with her. Collins was outside washing the car, in his shirtsleeves. It was rather a pleasant sight. He saw her there and waved with a smile.

Jane thought Bridget was quite right not to leave such a place. Danby had everything it needed right within its walls.

Chapter Thirteen

Cecilia knocked at the door of Primrose Cottage and waited for a moment, but a cloud of silence still seemed to linger around the old house, heavy and sad. Mrs. Price had only lived there a few days, yet her absence turned it to an entirely different sort of place, her bicycle abandoned by the gate, the windows shuttered.

Cecilia wondered if she should just leave the house to its mourning, yet Anne Price had sent a note at breakfast asking if she could call if she came to the village. Cecilia only had the morning hours before she would be missed, since she had promised her mother she would help with the infernal bazaar that afternoon.

She stepped back onto the garden path to study the upstairs windows, where the bedrooms lay. They were all shuttered, blank, and she thought maybe the Prices had already departed. But they surely couldn’t leave until after the inquest, and Anne had asked her to call.

She was just about to knock again, when the door opened suddenly. Nellie stood there, her hair loosely pinned under her cap, eyes reddened.

“Oh, Lady Cecilia,” Nellie sniffled, giving a crooked bob of curtsy. “I’m so sorry if you’ve been waiting, I was just—just packing a few things upstairs.”

Packing away Mrs. Price’s belongings, no doubt. No wonder the poor girl looked so distracted. “I’m sorry if this is a bad time. I had a note from Miss Price and thought I would come by while I was in the village.”

“She’s just gone out. That sergeant with the crooked nose came to fetch her.”

“Sergeant Dunn? Did he say what he wanted?”

“Just had a few questions, I think. She shouldn’t be long, Lady Cecilia. Would you like to wait in the sitting room?”

“If it’s not too much trouble. Thank you.” Cecilia followed Nellie through the foyer and down the narrow corridor. She glimpsed the dimly lit staircase and tried not to remember how Mrs. Price had looked lying there, like a broken doll. And now she seemed to have left a broken family and Union in her wake.

The sitting room looked as if no one had been there at all since Cecilia last sat there with Anne. The table was spread with wineglasses and loose papers, the fireplace in ashes. The air smelled stale and close.

“Is Miss Black still in residence?” Cecilia asked. “I would have thought everyone would want to stay until the whole matter is, well, resolved.”

“So they do. Miss Anne just wanted me to get a head start on the packing, for when it’s all solved at last. Miss Black is asleep upstairs. She couldn’t sleep at all last night. Miss Price called Dr. Mitchell to give her a draught this morning. We had hoped she was feeling better, but now . . .” Nellie waved her hand in a helpless gesture.

“I’m sure she will feel much better once she can return to her own home,” Cecilia said, and she wondered where that was.

“The inspector says we have to stay for the inquest.”

“Of course. Has Mrs. Winter been back to Primrose Cottage?”

Nellie laughed humorlessly. “Her? Not today. Mr. Winter came around last night, trying to take Mrs. Price’s pearls. For safekeeping.”

Mr. Winter didn’t seem to waste any time, then. “I suppose they have to stay, as well. The Winters.”

“I guess so, but you’re quite right, Lady Cecilia—we’ll all be better off when we can leave and go home.”

“Where is your home, Nellie?”

“Kent, once upon a time, but I’ve lived in London since I started to work for Mrs. Price. It’s wonderful there, so much happening all the time! Especially with a mistress like Mrs. Price, you know, never a dull moment.” Nellie smiled wistfully.

“Have you been with her long?”

“Almost five years now. Since before she moved to her own flat, back when she and Mr. Price lived together.”

Cecilia was quite sure Nellie had many fascinating tales to tell about the Price ménage, and the Union’s work. “So the whole family lived together back then?”

Nellie shook her head. She unlatched the window and let in a breeze of fresh air, waving away the stale stuffiness. “Mrs. Winter was just married and gone, and Miss Price was getting her own flat after she finished school. It’s a good thing, since she and her father quarreled all the time.”

“I suppose he didn’t approve of the suffrage work.”

Nellie snorted. “He worries about the gossip, like Mr. Winter. That’s all they care about. What people think of them and their careers.” There was a sudden thud upstairs, as if someone was walking on the old floors. “I should look in on Miss Black.”

“Yes, of course. I’ll be fine waiting here, Nellie.”

As the maid left, Cecilia plumped the cushions on the settee by the window and studied the room. She noticed Cora’s cards on the table and wondered if maybe she had tried to contact Mrs. Price using her medium skills. She went to straighten them and saw that no one had yet cleaned away the torn papers strewn on the tablecloth: . . . regret this . . . never tell . . . improper dalliance . . . she read on the papers.

Improper dalliance. Fascinating. Cecilia studied the scrap and saw that the handwriting was dark black and straight, the paper cheap. There was the faint whiff of some kind of scent, not the heady roses Mrs. Price wore, more grassy and green. The edges were roughly torn.

She glanced back at the fireplace, which hadn’t been properly cleaned out and relaid. There were scraps among the ashes, too, and she remembered how Anne had stirred up the fire on the day Mrs. Price died. She herself had glimpsed some papers in the ashes that day.

She heard the squeak of the garden gate and looked out the window to see Anne walking toward the door. She wore a purple walking suit, a black band around the sleeve, and her head was ducked beneath a narrow-brimmed hat, as if she was deep in thought. Cecilia wished she could stuff the papers into her handbag to show Jane later, but she had left her bag across the room on the settee, and she didn’t want to be barred from Primrose Cottage for snooping. She rushed to put the scraps as she found them back on the table and sat down on the nearest chair, her hands folded in her lap.

“Oh, Lady Cecilia,” Anne said, unpinning her hat as she stepped into the sitting room. “Thank you for calling. I’m sorry to keep you waiting.”

“Not at all. I haven’t been here long,” she answered. “Nellie told me Sergeant Dunn came for you. Is there any news?”

“It seems some well-known thief was found with Mother’s ruby ring, and I was asked to identify it. Perhaps there was merely an interrupted break-in, after all.”

Cecilia thought of the man Mr. Talbot thought he saw walking by with the sack. “Was the ring the only thing they found with him?”

“Yes, from here anyway. I suppose he didn’t have time to take anything else.”

“So is there still to be an inquest?”

“Colonel Havelock insists on it, as it was a suspicious death. I suppose that’s part of why I needed to speak to you, Lady Cecilia.”

“Because I may be called on at the inquest?”

“Yes, but also to invite you to a memorial we’re going to have for Mother at the Guildhall. Most of the Union ladies have returned to their homes, but some of us must stay until things are resolved, and we want to do something to keep us occupied, to continue Mother’s work.”

“That sounds like a wonderful idea. Of course I’ll be there. Do you need any assistance? I could make arrangements with the florist’s shop here in the village. They do beautiful work and can get a wide variety of blooms in very quickly.”

“That’s very kind of you, Lady Cecilia. I also wanted to ask if you might like Mother’s bicycle.”

“Her bicycle?” Cecilia said, thinking of the way it wobbled and swayed under her when she first tried to ride it. Could she conquer it in the end, in honor of Mrs. Price?

“Yes. I know you’re just now learning to ride, but having your own vehicle for practice will surely help. And she’d like that so much. I hate to think of it going unused.”

“I will certainly ride it! And think of your mother when I do. Thank you, Miss Price.”

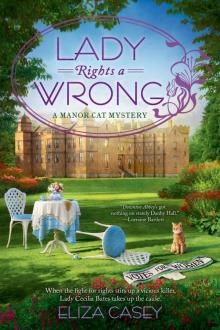

Lady Rights a Wrong

Lady Rights a Wrong