- Home

- Eliza Casey

Lady Rights a Wrong Page 10

Lady Rights a Wrong Read online

Page 10

Anne nodded. “You’re quite right, Lady Cecilia,” she said softly.

“I think this may be one time we might indulge in a spot of wine ourselves, even if it’s still morning,” Cecilia suggested, and Anne nodded. As Cecilia left the fire and poured out two glasses of a port she found on the sideboard, she noticed a pile of torn papers near Cora’s séance paraphernalia. Curious, she peered closer, smelled a faint perfume of sweet lilacs, and saw a few words in smeared black ink: . . . forced to take action . . . hope it does not come to this . . . And there was a bit more, harder to make out.

“Is everything all right, Lady Cecilia?” Anne said.

Cecilia nodded and pushed the papers half under the box of tarot cards in case a closer look would have to be taken later. She handed Anne the glass.

“To Mother,” Anne said, and Cecilia nodded with a sad smile.

“To Mrs. Price.”

They sipped at their wine in silence for a moment, listening to the comings and goings outside the door, the sounds of sobs from Nellie in her room upstairs, and slowly, Anne seemed to steady herself. She sat up straighter and shook her head.

“Thank you, Lady Cecilia,” she said. “You are kind. Mother did say you were a good sort of lady.”

“That was very nice of her,” Cecilia said, and sat down next to Anne on the settee. “So you heard nothing at all last night, Miss Price? After your brother-in-law’s car left.”

Anne shook her head. “I read for a while, then went to sleep. I’m a fairly heavy sleeper. I thought I heard Nellie moving about in Mother’s room, but that was all.”

Cecilia thought of the man Mr. Talbot had seen walking away with the sack. “Perhaps there was another attempted theft, and Mrs. Price surprised the thief this time?”

Anne shrugged helplessly. “Possibly. Mother would insist on taking her jewels everywhere she went, and she could be a bit—well, careless with them at times. I noticed she was not wearing her ruby ring last night, and she wore it all the time, despite her estrangement from my father. But she did have many enemies. Any of them could have gotten in late at night.”

“Enemies?”

Anne took another sip of her wine. “Those who possess all the power, Lady Cecilia, will never give it up easily, simply because it is the right thing to do. They will fight us with everything they have to keep us as slaves, cleaning their houses and raising their children. Those of us who fight back, who stand up for ourselves, are hated simply because we insist on our own humanity. So yes, my mother did have enemies. Starting with my father and sister, I’m afraid.”

Before Cecilia could ask her more about those shocking words, Colonel Havelock and Sergeant Dunn appeared in the doorway, followed by two local constables. They looked most solemn. Jane and Cora were behind them, Cora leaning heavily on Jane’s shoulder. Jane held Jack in her other arm, but he looked very much as if he wanted to leap down and explore.

“My apologies, ladies, but if everyone could remain here for the time being, I would be most grateful,” the colonel said. “I am sure we will have more questions after a longer look around the cottage.”

“May I take Miss Black upstairs to change her clothes, Colonel Havelock?” Jane asked. “She also has not been well and tells me she needs to take her medication.”

“Yes, of course, if you tread carefully, Miss Hughes. And perhaps you can ask Mrs. Price’s maid if she will kindly leave her room soon,” the colonel said. “Sergeant, will you escort Lady Cecilia and Miss Price outside to the garden for a moment?”

“Certainly, Colonel,” the sergeant said, flashing Jane a shy smile as she led Cora past him. “Ladies, if you will follow me?”

“Perhaps I might just fetch the decanter, Sergeant? As it seems we will be here for a while.” Anne sighed and drained her glass before setting it carefully on a small table. “Maybe we should ask Cora to use her spirit medium skills to ask Mother what happened.”

“And what do you think Mrs. Price would say?” Cecilia asked.

“I think I know what Cora would claim Mother said.”

“What do you mean?”

“Cora and Mrs. Palmer have been thick as thieves lately. And they have their own ideas of how the Union should be run.”

“And those ideas were not your Mother’s?” Cecilia asked. Could Union politics really have something to do with Mrs. Price’s death? She didn’t know much about Harriet Palmer, but Cora seemed to worship Amelia.

Anne opened her mouth, but then she seemed to think better of whatever she had been about to say. She shook her head and took up the decanter and her glass before heading toward the door. “We all have our own ideas about how life should be run, do we not?”

A scream suddenly erupted through the cottage, shrill and full of terror. “Mama! No! How can this be?” a woman shouted.

Anne groaned. “I see Mary has arrived.”

“Mary?” Sergeant Dunn asked in a bewildered tone.

“My sister,” Anne said.

Cecilia ran to the sitting room door to see that Mary Winter had indeed “arrived.” Her hair was loosely pinned atop her head, and she wore a lace jacket hastily thrown over a pink muslin morning gown, as if she had started her morning toilette and been a bit interrupted. There was no sign of her husband.

One of the constables held her back from the staircase. She fell to the floor, her shoulders heaving. Cecilia was strangely reminded of a performance by Mrs. Patrick Campbell in Bella Donna she had seen at the Lyceum that summer.

Anne seemed to agree as she peered down at her sister with an exasperated frown. “Oh, Mary, do stop that caterwauling and come outside with us. You are not being helpful in any way.”

Mary stared up at her sister with an equally exasperated expression. “How can you be so heartless at a time like this, Anne? You always were so cold! Not human at all. Our mother is dead.”

“Our mother who you have refused to speak to for months,” Anne said. “You only appeared here because you and Monty want something, though who could ever say what.”

Mary’s face contorted, and she jumped to her feet to stalk toward Anne. She didn’t even seem to see the constable or Cecilia. “You know what she did to us, to Monty and me! How could I talk to her after that? But I never wanted to see her dead! I’m not ruthless like you and your unnatural friends.”

Jane and Cora reappeared, Cora dressed hastily in a white skirt and shirtwaist, her hair twisted back. Jack hissed a bit at the commotion but was quickly shushed by Jane. Cora stepped between the warring sisters, her hands held up. “Please, not now!” she cried.

“Colonel,” Cecilia said, fearing things were about to become even more dramatic. “Perhaps Jane and I could take the ladies to the tea shop while you finish here? I’m sure they will be ready to answer any questions you might have afterward.”

Colonel Havelock looked quite relieved. “I’m sure that is acceptable, Lady Cecilia, thank you.”

“Miss Price, Mrs. Winter,” Cecilia said, taking them each firmly by the arms and leading them out of the cottage, keeping them facing away from the terrible sight at the stairs. Jane and Cora followed close behind, Jack stuffed back into his basket and mrowing irritably at it.

The breeze outside was fresh after the close, coppery tang of the cottage, and Cecilia took a deep breath as she kept a firm hold on the warring Price sisters. But her relief was short-lived when she glimpsed a man at the gate, a short gentleman in a cheap tweed coat and bowler hat, with the telltale notebook and pencil of a reporter. His face lit up when he saw them.

“Miss Price! What’s happened to your mother?” he called. “Is it true she was found bludgeoned in a pool of blood? Do you suspect anti-suffragists?”

Cecilia gave him a freezing look, learned from her mother when some social parvenu tried to get too close, and marched their small party past him, slamming the garden gate behind them. He

fell back, but she feared he was just the vanguard. She thought Danby Village was going to get much less sleepy very soon.

Chapter Eleven

Oh, you poor dears,” one of the Misses Moffat clucked as she led their strange and forlorn little party up to a private parlor above the public tea shop. “What a terrible morning you have had! What an inspiration Mrs. Price was. You just sit down here; no one will bother you in my shop. There’s a Victoria sponge with raspberry sauce, fresh from our kitchen. I am sure it will fortify you.”

As she left, one of the pink-aproned maids placed the tea service on the table, gawking at them wide-eyed. But she was obviously under strict instructions from her employers and quickly left them alone despite her curiosity.

It seemed Mary and Anne had already burned out their ire with each other, at least for the moment. The silence of the parlor, muffled by heavy pink and white satin draperies at the bow window, was almost deafening after all the drama and clamor outside, as thick as the Misses Moffat’s famous clotted cream for scones. Anne and Mary did not look at each other at all.

Cecilia and Jane exchanged a quick grimace. Cecilia wasn’t really sure what to say or do now. Ever since childhood, she had been taught the proper behavior for every possible social situation, every awkward moment or sudden challenge. A burned menu item at a dinner party, the sudden appearance of royalty, an unwanted marriage proposal. Taking tea with two newly bereaved but warring sisters had never been taught by her governess.

Miss Moffat brought the cake herself, and Cecilia played mother, filling the teacups and passing them around the table. Anne and Mary smiled briefly at her but still did not look at each other.

“You live in London, I believe, Mrs. Winter?” Cecilia said, trying desperately to find something to talk about that wouldn’t make Mrs. Winter cry again.

Mary nodded. “In Ebury Street. With my husband, Mr. Montgomery Winter. He is a solicitor.”

“And yet you managed to come to Danby Village so quickly,” Anne said dryly. “Just before Mother’s passing.”

Mary scowled. “That was a hideous coincidence, and you know it! Monty and I wanted to make amends with Mama, and I fancied a bit of country air. I never expected to find it like this. I wrote to her before we came!”

“I never saw any letter from you,” Anne said.

Mary pursed her lips. “I suppose you do read all her post. I wouldn’t be surprised if you kept my letter from her on purpose.”

“Cora takes care of Mother’s correspondence now, don’t you, Cora?” Anne said. Cora stared at her in silence, and she went on, “I am sure Mother would have mentioned hearing from you after all this time. Why would you be writing to her now, anyway? Making amends, ha. You and Father would never do such a thing.” She pushed away her plate of cake without taking a bite.

Mary looked furious. “I am not the one who needed to make amends! You know what happened because of Mother. Because of you both, and your horrid ideas. You behave like such barbarians, parading around in public, neglecting your proper duties. Poor Father! How he has suffered, just as Monty and I have, because of you.”

“Father, suffering?” Anne said with a bitter little laugh. “He tossed Mother out.”

“He was the head of our household, and she would not listen to him! It was his right. We could all have been so happy, so socially secure, if only you and Mother had tried. Instead it’s all just . . .” Mary’s eyes filled with tears, and she stuffed a large bite of the cake into her mouth.

Anne gave a tired sigh. “Is that why you’ve come, then, Mary? To tell Mother again what a misery she had made of you and your precious, prosperous Monty, all because she insisted on being herself, her own person? You could have saved the effort.”

“We only wanted to see if common ground could be found somehow,” Mary said around her cake.

“Where is Monty today, then?” Anne said. “I don’t suppose he lets you wander around by yourself now.”

“Of course not! I am a proper lady, something you would know nothing about. He is at the cottage we rented behind the church. He was still asleep when I heard about poor Mother. He has not been sleeping well lately, and it’s no wonder. I had wanted to come see Mother this morning anyway, before I heard she had—died. I hoped this early she would be—well . . .”

“Sober?” Anne said shortly, and Mary let out a sob.

“That is not fair,” Cora cried. “You know Mrs. Price was not like that. She would never have had so much to drink that she . . .”

Anne sighed, and Mary started crying again. Jack hissed in his basket.

Cecilia handed Mary a napkin and patted her hand. “It must have been a terrible shock to hear what happened, Mrs. Winter.”

Mary nodded and took another bite of cake. “A woman cleaning in the churchyard told me as I was walking past. I hadn’t been able to awaken as early as I had hoped. I slept so heavily after Monty sent me home. That poor woman in the churchyard, she didn’t even know who I was when she told me, but she was just so—so gossipy. We are always such a scene of tittle-tattle wherever we go now! It is quite unbearable.”

“I suppose not so unbearable for Mother now,” Anne said shortly. “She can’t hear it. And now you and Monty and Father won’t have to put up with it any longer.”

Mary sniffled even harder, and Anne sipped at her tea. Cora looked mortified, and Jane sadly shook her head. Cecilia thought she could tell what Jane was thinking—the Prices were an odd clan indeed.

She thought of her own parents, how they sometimes drove her quite mad with their old-fashioned ideas, her mother’s matchmaking attempts. Her grandmother’s bossy, seemingly all-knowing ways. And Patrick—she sometimes wondered how they came from the same parents, he was so intellectual, so distracted. She had grown up knowing the world of Danby Hall worked in a certain way, and she had her place in it, no matter how she fought against it. Yet she had also known they loved her, they wanted her happiness as they saw it, and she loved them in return. They had their quarrels, their misunderstandings, but never anything like this icy indifference and animosity between the Price sisters.

What had happened between Amelia Price and her husband? What drove Mary and her husband so far away from her mother and sister? Was it really only Mrs. Price’s suffrage work? And what was Mary doing in Yorkshire now?

There was a knock at the door, and Sergeant Dunn peeked into the parlor. Cecilia was suddenly rather glad to see his battered, crooked-nosed face. The anger and grief that tightened around them in that small parlor was starting to cut off her breath.

“Inspector Hennesy is on his way,” the sergeant said. “He wires that he will set up an office of sorts at the Crown, if you would care to speak with him there later today, Miss Price, Mrs. Winter. I know he will want to talk to you, as well, Lady Cecilia.”

Anne nodded and pushed back her chair to march out the door, past the sergeant. “Cora, perhaps you would come with me? We can start looking through Mother’s papers.” Cora nodded and followed her out.

Mary blew her nose in the pink napkin. “I must go to my husband,” she said.

“Let me walk you there, Mrs. Winter,” Cecilia said. “You said your cottage is near the church, and I need to stop there anyway. Sergeant, perhaps Miss Hughes and I could speak with the inspector at Danby at his convenience? I must be getting home soon; my mother will be wondering where I am. And Jack will want his meal soon.”

At the mention of Danby Hall and the countess, the sergeant hastily nodded. “Of course, my lady. And Colonel Havelock said he will send word as soon as the inquest is arranged.”

“Thank you, Sergeant.” Cecilia took Mary’s trembling arm and led her gently back to the street. Luckily, there was no press waiting there; they were probably all gathering at the cottage. She remmebered that Mrs. Winter had said she was on her way to see Mrs. Price that morning when she heard the news. “I am terr

ibly sorry you weren’t able to see your mother this morning, Mrs. Winter.”

Mary sniffled. “It is like a curse, isn’t it? Feelings must go on forever unspoken, love lost and buried by hate.” She pressed the back of her hand to her mouth and shuddered.

Cecilia was rather fond of a penny dreadful novel herself, all curses and tragedy, but she wondered if perhaps Mary wasn’t laying it on a bit too thickly. She thought again of Mrs. Patrick Campbell.

“I’m sure your mother knew you cared about her, just as she must have cared about you, no matter what passed before,” Jane said.

Mary gave her a startled look. “Cared? My mother never cared about me. She never cared about anything except herself.”

“Mary! Mary, my darling, I just heard,” a man called out, and Cecilia saw Monty Winter running along the pathway that led around the churchyard. She was reminded again that if she had ever imagined what a solicitor married to a lady like Mary Price would be, this was him. Solid, respectable, his hair pomaded to a shine, his suit perfectly tailored. Even as he rushed toward them to take Mary into his arms, all tender, marital solicitude, Cecilia thought it was all a perfect picture. Mary stiffened a bit, but then gave him a watery smile, turning her cheek to his kiss.

“It is true, then? Your mother is—deceased?” he said. “How is that possible?”

“She—she had a fall,” Mary answered. “And there is some inspector who wants to speak to us later, so horrid.”

“Speak to us?” Monty said, his concerned-husband mask slipping a bit as if he contemplated a scandal. “Surely, he must know we can be of no help! We only just arrived here.”

“Then I’m sure he will let us return to London soon. After I make sure proper arrangements are in hand. Anne can’t be trusted with such things.” Mary smiled again and half turned to Cecilia. “Darling, this is Lady Cecilia Bates, from Danby Hall. We saw her ever so briefly at Primrose Cottage. She so kindly offered to escort me home after this morning’s awfulness.”

His expression immediately changed to a charming smile. “Lady Cecilia. How very thoughtful of you to see to my wife. I am sure none of this can be of interest to you.”

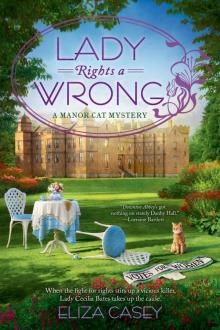

Lady Rights a Wrong

Lady Rights a Wrong